When the new constitution for the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) was written, its main aim was to resolve the conflicts between warring factions that had brought the country to its knees. In the peace talks of 2002 and 2003, convened to assuage the demands of multiple interest and ethnic groups, it was agreed that the DRC would adopt something approaching a federal model. Each province would have its own government, elected assembly, revenue-raising powers, and a governor appointed by the provincial assembly. The existing 11 provinces were to be subdivided to make 26. These agreements were all incorporated in the final constitution of 2006.

Decentralization, however popular it might be with the electorate, inevitably reduces the political and economic power of central government. For this reason, national leaders often only adopt decentralization policies under duress, and the DRC is no exception. This lack of incentive often reduces the speed at which legislation is drafted and adopted, as well as the level of funding allocated for the transfer of resources and staff. By the DRC government’s own admission, today—seven years after the new constitution was adopted—seven major Acts of Parliament related to decentralization remain to be enacted. Subdivision of the existing provinces has been postponed indefinitely.

The Programme de Bonne Gouvernance (PBG), a U.S. Agency for International Development project implemented by DAI in collaboration with RTI, has as one of its objectives the strengthening of decentralization in the DRC. The project works with national government and the National Assembly, with four provincial governments and assemblies, and with 12 local governments. One of its tasks is to provide technical assistance to central government regarding decentralization, but from the September 2009 launch, progress was slowed by delays on the central government side.

Given this situation, we asked ourselves: Is it possible instead to work from the bottom up to move decentralization forward? Our provisional answer to that question is yes.

Three Working Principles

- Proceed step by step to ensure local ownership of the process. Each procedure we proposed was entirely new and had first to be welcomed by the local people. Before beginning any workshop or other initiative, we made sure that the leader (the mayor, for example) was 100 percent behind us. Remarkably, this was the case most of the time, even when his or her interests appeared to be adversely affected. We ascribe this phenomenon to the novelty of receiving international assistance—previously unheard of at the local government level—and the fact that these leaders recognized that participation and transparency can be political assets.

- Avoid expensive technical assistance. In all cases, the consultants used have been Congolese nationals, and though we prepared guidelines on how the workshops were to be implemented, the consultants made them their own. Working in local languages in many cases, they produced tangible results by building on a bold core message: “You are the people who must manage your own affairs. You have to take responsibility for it, and cannot rely on us to either give you the answers or to support you.”

- Keep it simple and replicable.

It is important to note that there has never been any independent local government in the DRC. Local administration was, until recently, simply an arm of the central state. Mayors, bourgmestres (heads of communes), and chiefs (in those areas where there are no hereditary chiefs) are appointed by the President, and local government staff are part of the national civil service. There are no local councils, and although elections for local councils were originally scheduled for 2009, these have repeatedly been postponed and are unlikely to be held until 2015 or 2016.

However, under the 2006 constitution, local government entities—known by their French acronym as ETDs—are legally autonomous. They can raise their own funds and manage their own affairs. This newfound independence provided a foot in the door for new and innovative decentralization tactics.

The Tools And The Process

Our strategy was ambitious. Implementation of the new bottom-up process started in April 2010, after a baseline survey undertaken earlier in the year. We wanted to strengthen local government entities in three ways: introduce citizen participation in decision making and monitoring of ETD performance, increase local governments’ own revenues, and improve service delivery. We hoped to nurture a virtuous cycle of improved participation.

The first step was to develop action plans. The objective was to prioritize development projects (typical favorites were rehabilitation of schools and health centers) with approximate costing and implementation plans, and establish a joint civil society and public sector committee to monitor the projects. In contrast to local development plans that typically depend on consultants (at considerable cost), our approach was to use the knowledge within the community and debate decisions regarding needs and priorities in a participatory workshop.

The second step was to analyze the financial management of the ETD, discuss the results in, again, a participatory setting, and agree what should be done. Here, another monitoring committee was elected that included community members and local government staff. Implementation of workshop recommendations is monitored by PBG staff, and there are annual workshops to review progress. At the same time, participation in the financial affairs of the ETD has been steadily widened to include small and large businesses, tax collectors, and other stakeholders.

The next stage was more radical: participatory budgeting and citizen monitoring of public services such as schools, health care, sanitation, and road maintenance. The former began more than a year ago and has been implemented by all 12 participating ETDs; citizen monitoring is now under way, and we hope that within a year it will achieve the same remarkable level of acceptance as participatory budgeting—thereby strengthening the role of the community as watchdogs and stimulating improved service delivery.

Lastly, to improve service delivery, we introduced a totally new tool for the DRC—public-private partnerships—which have allowed ETDs to attract private investment to improve and manage public facilities at no cost to local government.

Promising Results

PBG’s decentralization initiative has shown some striking results:

- Without exception, the “own revenues” of participating ETDs—that is, funds they raise themselves, as opposed to intergovernmental transfers—have increased substantially, in some cases more than doubling. These revenues are derived from a wide range of sources including business licenses, market fees, vehicle licenses, and building permits.

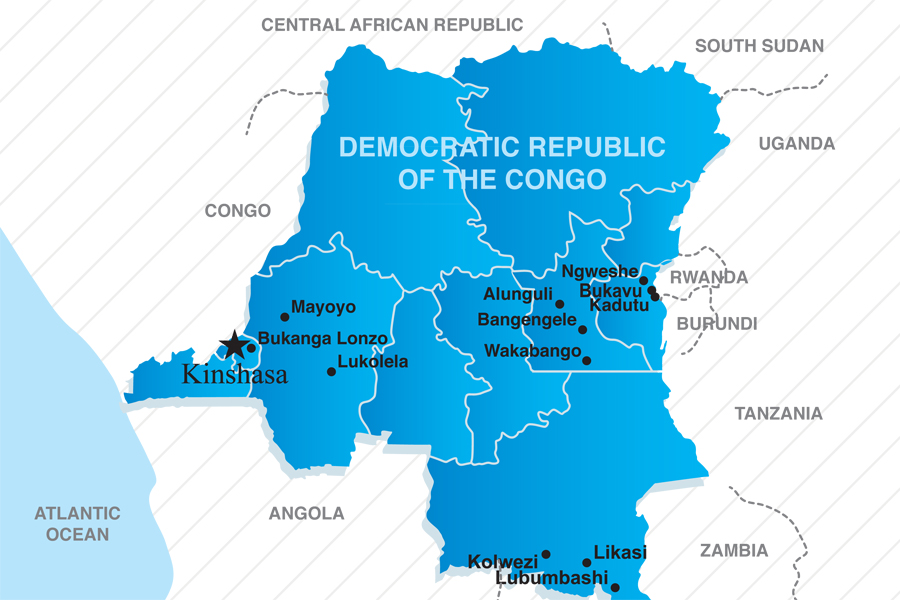

- Private enterprises have invested $300,000 for a market project and $150,000 for a community hall in Katuba (a commune in Lubumbashi), and a third project to rehabilitate a swimming pool and leisure center in Likasi is in the pipeline—without spending a penny of public money.

- The Governor of one participating province, South Kivu, has required all ETDs to conduct participatory budgeting. (A World Bank project active in the province also deserves credit for this outcome.)

- One particularly enthusiastic ETD, Ngweshe, announced an open session for all citizens to participate in the budget. People came from hundreds of kilometers away and the session lasted all night and the following day—24 hours in all. The resulting budget, although higher than the regular one, was so impressive that the ETD received additional funding from the province. Our PBG project did not fund this event in any way.

- The ETD of Kaziba, which is not part of PBG, seeing the results achieved by our consultant in terms of financial management and citizen participation, paid him from its own funds to provide the same service there.

It is too early to draw final conclusions, but the evidence suggests that PBG’s low-cost, participatory approach is generating real interest across the DRC. The next phase is to take staff from the central government’s decentralization unit into the provinces so they can see the results and consider adopting our approach more widely.

Eventually, bottom-up decentralization may prove to be less of a contradictory concept than it sounds.