In the years leading up to 2020, school enrollment in Honduras suffered a steady decline. In 2018, 81,000 students (4.06 percent) dropped out. In 2019, some 105,000 students (or 5.39 percent of the total) abandoned their education to seek work, join gangs, or migrate without documents to the United States. Approaching the opening of the new school year in February 2021, education officials realized that they would face an even greater crisis during a pandemic and in the wake of hurricanes Eta and Iota. Already, school-aged children were migrating north.

In response, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) Asegurando la Educación (Securing Education) project launched the Early Warning and Response System (EWRS), a mechanism that helps educators identify students on the brink of dropping out and keep them in school. Asegurando—a project designed to reduce school-based violence and improve access to education, academic performance, and retention in Honduras—designed the EWRS around an existing Ministry of Education system that helps enroll returning migrant children.

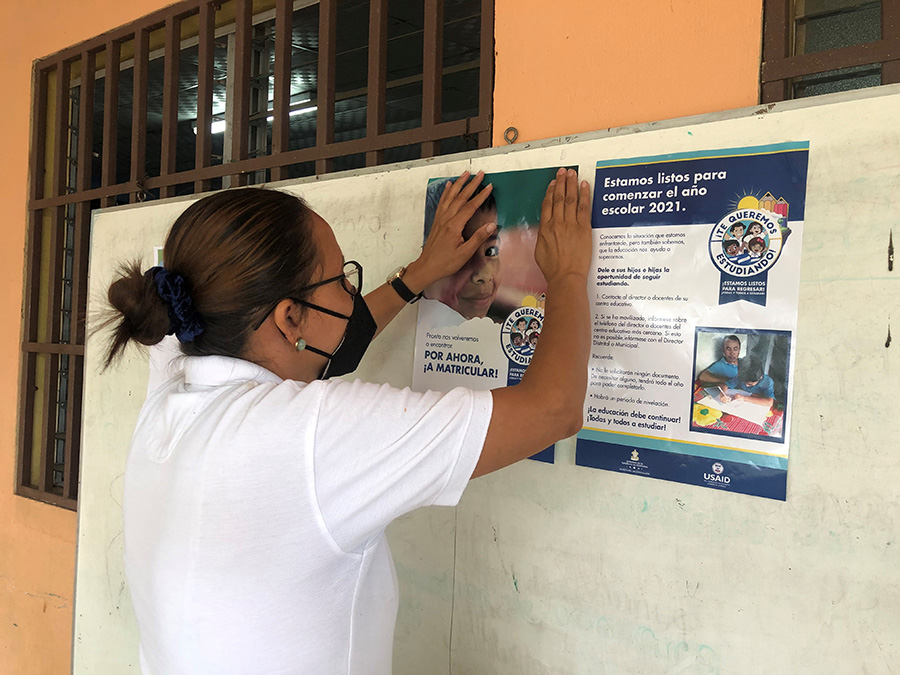

The project team conducted an extensive campaign to encourage students to re-enroll in school. Photo: USAID Honduras Asegurando.

After the ministry opened registration in early February 2021, enrollment gradually climbed over the next several weeks in March, and Asegurando provided weekly updates to the Ministry through a newly developed EWRS dashboard. The dashboard offers decisionmakers a user-friendly visualization of enrollment and retention figures across the country so that officials can respond to challenges in any given region.

But on March 19, some five weeks after school registration re-opened, the enrollment rate had only reached 83 percent of the statistically generated forecast. Minister of Education Arnaldo Bueso called for an emergency Government of Honduras cabinet meeting to address the historically low rate, calling it an “education crisis.” He suggested that many Honduran students were migrating to the United States instead of enrolling in school. He called on the cabinet members to support enrollment efforts and asked Asegurando to present the EWRS.

Part of the campaign included visits to households to determine whether students were able to return. Photo: USAID Honduras Asegurando.

How it Works

The EWRS equips education stakeholders with the tools, protocols, and training to identify early warning signs of school abandonment and out-migration, and then mobilize resources and take action to keep students in school, studying, and advancing toward graduation. Trained teachers, counselors, and volunteers follow a series of protocols to recognize student behaviors and patterns and then respond by securing academic tutoring, individual or family counseling, or other interventions that facilitate continued education. The system also seizes certain opportunities within the education cycle when students are most vulnerable—enrollment, mid-term and final exams, and formation of migration caravans—to conduct back-to-school or stay-in-school campaigns.

Because of the education crisis and high rate of irregular out-migration, Asegurando was simultaneously attempting to curb out-migration by increasing enrollment, all while field testing the theoretical model in 50 schools. Normally the process of designing, field testing, finalizing manuals and tools, and rolling out a new Asegurando intervention takes two or three years. Our mentoring program, for instance, took one year to field test and a second year to roll out. Likewise, our sports-based social-emotional learning and cognitive behavioral therapy programs required two years. In the case of the EWRS, potentially Asegurando’s most complex activity, the project team found itself flying an airplane that was still under construction.

Nationally, the EWRS had its desired effect. The data shared through the dashboard stimulated action at the highest levels of government. The National Institute of Migration; the National Center for Social Sector Information; the National Directorate for Children, Adolescents, and Families; the Honduras Chancellery; and the Ministry of General Government Coordination all streamlined identification processes and the information flow of returning migrant children so that the Ministry of Education can locate and re-enroll them.

The project team was able to garner more attention to the problem by conducting media interviews. Photo: USAID Honduras Asegurando.

The Education Ministry has also consolidated efforts of international nongovernmental organizations to identify and enroll young people who dropped out of school. With Asegurando support, 8,844 principals in 8,578 schools and 6,196 teachers in 1,692 schools have been trained on how to use the EWRS.

Additionally, 2,194 teachers and counselors from 947 high schools are now trained to provide youth and family telecounselling services that address emotional problems leading to school abandonment. Already, schools report that these counseling services are keeping vulnerable youth in school and off the path to irregular migration. Counselor Maria Esperanza Bustamente at Augusto Urbina Cruz Government High School in Tegucigalpa said the program has helped at least five emotionally struggling students who were on the brink of dropping out of her school. “It helps to slow migration… by helping them understand that studies are the only way to help them overcome any type of obstacle,” she said.

The team worked with 8,127 parents in the first two of what will be monthly webinars called School for Parents, which focuses on making a healthier home environment that helps students study. An Asegurando awareness campaign featured a contest that motivated students to internalize psychosocial messages through 25 social-emotional learning videos and then make their own two-minute video synthesizing one of those messages. Together, the School for Parents initiative and the video contest reached 1.1 million people on social media and an estimated 600,000 on national TV in three months.

Parents were included in the campaign through courses. Photo: USAID Honduras Asegurando.

Getting Kids Back in School

The EWRS field testing, which largely takes place in Asegurando’s 50 core schools in four cities, relies on hard work by hundreds of dedicated educators and volunteers. Asegurando has conducted distance learning workshops to help teachers better reach and engage students. It has helped organize back-to-school campaigns with flyers and signs at key traffic spots in neighborhoods surrounding schools, and street-by-street awareness-raising activities with messages broadcast via loudspeaker.

Early on, the teams raised donations for school supplies for disadvantaged youth. “Often a notebook, a pencil, and a pen can be the difference in whether a young person enrolls or not,” explained a principal in La Ceiba. Meeting these basic needs is particularly critical for older students who are embarrassed to show up for school without a notebook or pencil.

Local campaigns also generated TV coverage that helped spread the word on the value of education and the specifics of enrollment, such as dates and ways to enroll. Educators and volunteers utilized social media, word of mouth, and telephone calls to locate and encourage out-of-school young people to register for classes. These local teams went house to house speaking with parents and kids to motivate young people to return to school.

Asegurando is also conducting other activities designed to boost retention in 185 schools hosting 100,000 students. The project is delivering school supplies for nearly 50,000 young people and will provide workbooks in June and July for 50,000 students who do not have access to internet or electronic devices. Some 125 volunteers are conducting activities, such as tutoring students who are struggling academically to ensure they pass their tests and stay in school.

The project delivered much-needed equipment and materials to students and schools. Photo: USAID Honduras Asegurando.

Staying in School

EWRS’s early results demonstrate how well this fledgling system is working. Asegurando’s core schools enjoy an enrollment rate of 102 percent (of the statistically predicted enrollment number) while non-Asegurando schools in the same cities have a 90.7 percent rate. But initial enrollment was the easy part. The bigger challenge now is to keep those students in class, learning, and advancing toward completion of the academic year and promotion to the next grade in November.

Asegurando is aware that there are certain points within the school-year cycle that require additional emphasis and attention. The project has already met the challenges of pre-enrollment and enrollment. But two more upcoming periods are critical: before, during, and after the mid-term and final exams. These periods historically see larger numbers of older students dropping out because they perform poorly on exams. At the end of 2019, an educator at Mexico High School in Tegucigalpa reported that three of her high-risk students dropped out of school right before the final exams. She said that the parents had told their children that it was a waste of time because their grades were so low.

The final critical period is when migration caravans form. One principal in La Ceiba complained that a caravan announced its formation through WhatsApp and then assembled directly outside the school grounds. He felt helpless to prevent his students from joining. Asegurando hopes the EWRS will help schools conduct stay-in-school campaigns throughout these critical periods to focus on helping vulnerable youth perform better in class through tutoring and to promote the value of education and graduation as keys to securing a healthy and rewarding career inside Honduras.

Carlos Maradiaga is a Technical Advisor for Asegurando la Educación and Craig Davis is Chief of Party.