COVID-19 and its associated lockdowns have seriously disrupted economic activity, affecting at least 80 percent of the global workforce, according to the International Labour Organization. While such instability threatens livelihoods across the board, women are disproportionately harmed by the pandemic because it exacerbates existing inequalities, presents new challenges, and sets back recent achievements. But there are practical steps we can take to strengthen women’s economic position in the COVID-19 era—and beyond.

COVID-19 has affected women’s economic standing in several ways. In terms of income security, many women already find themselves in precarious labour positions, with lower earnings and limited access to social protection, making them more vulnerable in an economic downturn. Moreover, women work overwhelmingly in sectors hit hardest by the crisis, such as the entertainment, retail, agriculture, and tourism sectors, and the informal economy generally. Impacts are substantially worse in developing economies, with the few existing protection mechanisms under immense pressure and women facing significant barriers to accessing financial support, further extending their earning gap compared to men.

Access to finance is also a factor; in developing economies, women remain 9 percentage points less likely than men to have a bank account. They also have a smaller digital presence than men, which limits their ability to access financial services, many of which are increasingly offered digitally. This gap is increasingly salient and detrimental to women because digital financial services have prospered as a natural response to COVID-19’s social distancing imperatives, as discussed in our article on digital financial services during COVID-19.

Lastly, restrictions on movement have re-entrenched the traditional roles of women in the household and the workplace, further diminishing their economic position and opportunities. Home confinement has increased the burden of unpaid care work, which commonly falls on women. Lack of flexibility from companies results in women often being unable to work, rolling back hard-fought gains in female workforce participation while also disempowering women within the household. Disruptions in income mean that women and girls are often the first to experience setbacks due to pre-existing gender equalities that, for example, lead to boys’ education being prioritised over that of girls, or deprioritising the needs of women and their work.

These overarching issues—income loss, inadequate access to finance, and retrograde household changes—are likely to have longer-term impacts if not addressed, and risk setting dangerous precedents. COVID-19 has forced donors to re-evaluate how they allocate funding and adjust to the new context, so in the following sections, we look at how some donor projects have adapted their programming to help women cope with COVID-19 and how the insights gained from this experience can be used to rebuild women’s economic standing moving forward.

Safeguarding and Rethinking the Workplace

One of the keys to protecting women’s incomes during COVID-19 is ensuring that they can keep working. Several of the programmes we reviewed have adjusted their activities to support job continuity for women.

PEPE supports small and medium-sized enterprises that are women-owned or contributing to industrial growth. Photo: FCDO PEPE.

The Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO)-funded Enterprise Partners/Private Enterprise Programme Ethiopia (PEPE), for example, has provided medical equipment such as thermal scanners and thermometers and sanitation materials for industrial parks where PEPE has historically promoted the hiring of women. Providing this equipment—in coordination with an information campaign to boost knowledge about the virus and improve safety at work and in local communities—has raised health and safety standards to the point where women can work in a safe environment and maintain their source of income.

The FCDO’s Arab Women’s Enterprise Fund (AWEF) took a different approach, facilitating a workplace shift from the office to the home. AWEF had already been working on a pilot programme to demonstrate the business case for flexible working. AWEF had successfully partnered with Crystal Call Centres, a business outsourcing services company, to hire and test remote working with 21 home-based call centre workers—all women—to enable more women to participate in the labour market. When the COVID-19 lockdown hit Jordan, Crystel was able to rapidly pivot its operations and roll out a new model to the whole company in just two days, so that all its agents could work from home. The company credited AWEF with helping build the foundations that enabled it to keep functioning despite the COVID-19 restrictions.

For AWEF partners whose employees were not able to work from home—such as citrus packhouses—the programme supported hygiene and safety training that has helped them remain open, and offered courses on COVID-19 safety, hygiene, and safeguarding standards to ensure the well-being of female workers. The value of such interventions is, of course, not limited to the current crisis: providing safe, flexible, and bespoke working conditions is central to women’s continued participation in the labour market, pandemic or no.

AWEF expanded the reach of digital financial services to women. Photo: FCDO AWEF.

Good Information is Empowering

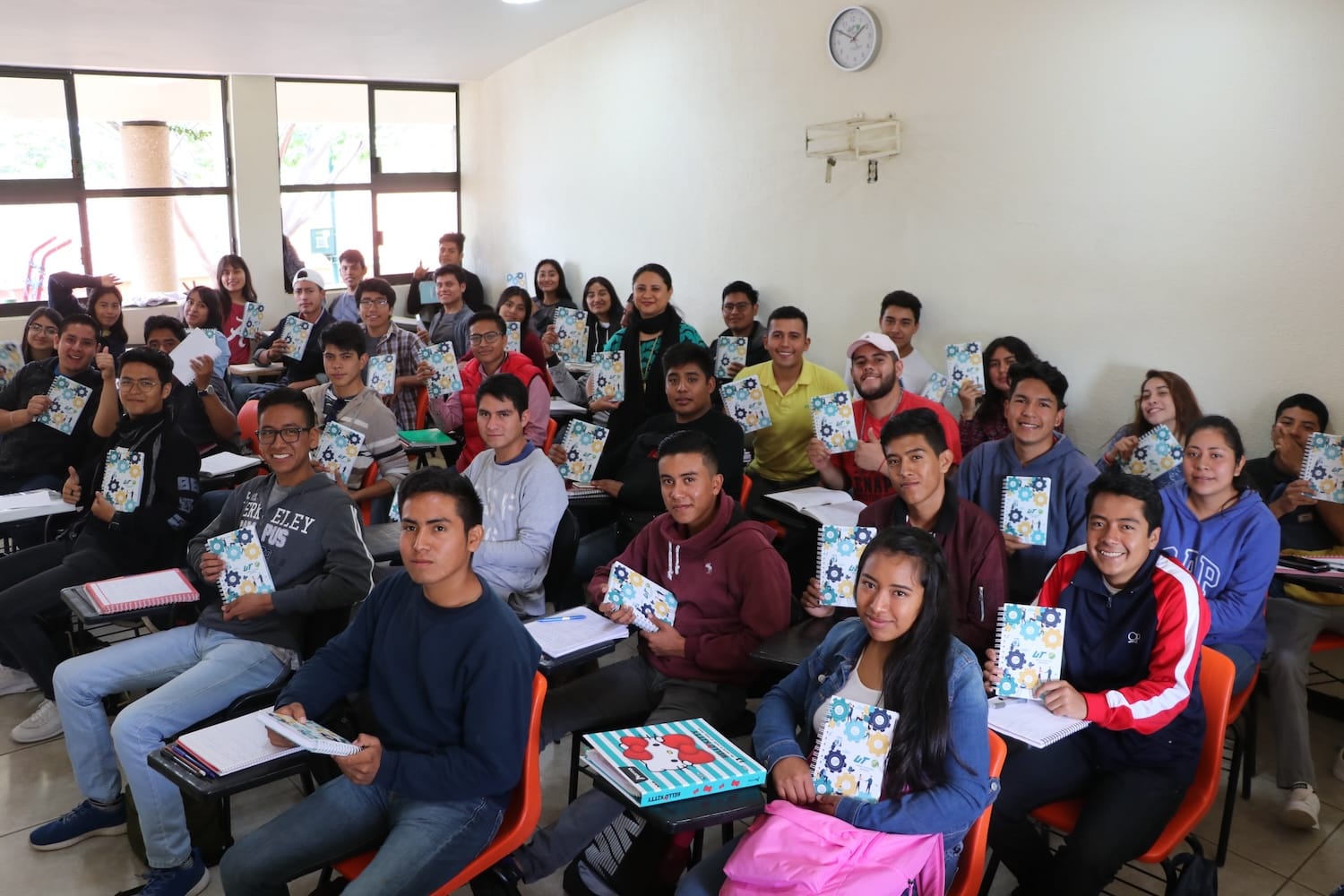

Many female workers run micro-businesses to support their families, but COVID-19 restrictions and deteriorating economic conditions pose significant challenges to women micro-entrepreneurs. The FCDO’s Mexico Financial Services programme has responded by focusing on the financial survival of vulnerable households engaged in subsistence-level enterprises, particularly female-led activities. It provides sanitary education geared to COVID-19 and builds families’ digital capacity to run their business, manage finances, and connect to supply chains and government assistance. One lesson learned: it’s important to equip households—not only small businesses—with the tools and know-how to manage their finances through the crisis and beyond.

The Mexico Financial Services programme increases bank usage to women and their families. Photo: FCDO Mexican Financial Services.

In Ethiopia, PEPE’s existing savings intervention, Tatari, had enabled factory workers to accumulate some savings before the pandemic, but many panicked workers withdrew their funds when COVID-19 hit. Subsequently, PEPE texted all Tatari members to encourage them to continue saving through this difficult time, which has reduced the level of withdrawals and will benefit women financially in the long run. Taking advantage of existing services makes it easier to reach target audiences and assist them in sustaining their livelihoods through crises. In the long-term, we hope that sharing such information can “nudge” people toward beneficial changes in behaviour and have a long-lasting impact on women’s autonomy.

Access to Finance Increasingly Means Access to Digital

Many development projects focus on women’s access to finance. As this access becomes further obstructed by the COVID-19 crisis, some are adapting to provide new products and services to women in order to support their businesses and ensure longer-term business continuity.

Through its partnership with Fawry, for example, AWEF had recognised the increased demand for digital payment services and launched a programme to recruit low-income, female Heya Fawry agents. These agents are equipped with point-of-sales (POS) machines to allow customers to make e-payments through the POS machines, rather than having to queue or travel to make household bill payments, insurance payments, pay education fees, top up airtime, or make purchases. During COVID-19, this business model has proven successful, and AWEF and Fawry are working on a microloan product to allow additional women to purchase POS machines and e-credit to enable them to become Heya Fawry Agents. These microloan products allow women to enter the market as a digital service provider, creating a source of income for women and enables women with a mechanism to safely make financial transactions, generating cost and time savings. The services are fully digitised and have been designed to better serve female clients within the community to sustain their livelihoods. Since the virus outbreak, AWEF’s partners have reported a rapid increase in the use of digital payment solutions, especially amongst female microentrepreneurs. AWEF has planned to further partner with a digital financial services provider to work on providing digital wage disbursement programmes, digital social cash transfers, and digital consumer microloans. In the short run, this makes it easier for women to access financial services and sustain an income in a COVID-19 context. In the long run, digital financial services are powerful tools for sustainable women’s economic empowerment.

In Mozambique, our programme works to expand financial inclusion. Photo: FCDO Mozambique.

In Mozambique, the Financial Sector Deepening programme has researched agent utilisation patterns to shed light on how agents can support vulnerable workers, especially women. Building on this research, it hired and trained female agents to recruit and educate people on accessing digital financial services. The result: a significant increase in registrations for M-pesa, a mobile phone-based money transfer, payment, and micro-financing service that provides economic opportunities for women and reduces gender disparities in access to digital financial services.

Plan for the Long Run

Donor programmes have adapted to COVID-19 in various ways: by incorporating new messaging or introducing new protection mechanisms; by supporting women in workplaces or women running home-based businesses; by focusing on the role women play in their households. But these short-term adjustments in programming can have long-term impacts on women’s lives and should not be designed and implemented only with a temporary or short-term vision. We have an opportunity in the urgency of this crisis to learn from the adjustments we are making and build upon them to create sustainable means of increasing women’s economic empowerment—in the long term and through the unforeseeable but inevitable shocks to come.

Daan Schuttenbelt Daan Schuttenbelt is an Associate Project Manager with the Economic Growth team in DAI’s UK office, working on projects in Mexico and Palestine.