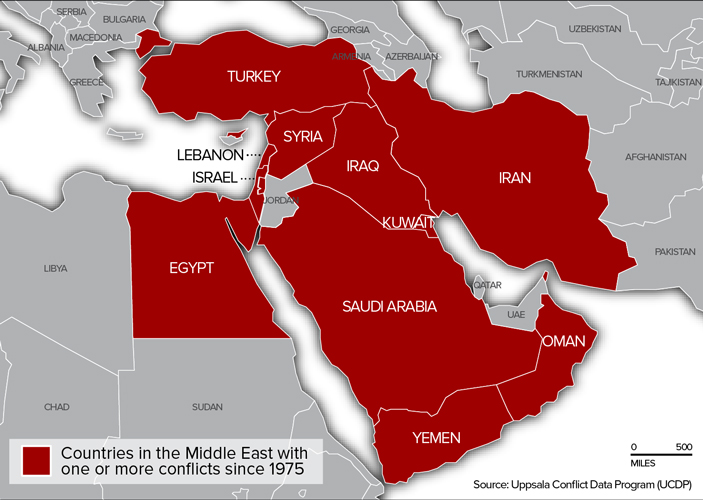

Much ink has been spilt by academics, analysts, diplomats, and the military regarding the causes of instability. But a broad consensus holds that environments with scant economic opportunities are fertile grounds for recruiting alienated and aggrieved young people to the cause of violent extremism. Taking that as a premise, it makes sense to pursue programming that bolsters economic resilience as part of an integrated strategy to counter extremism. In Jordan, we have an example where macroeconomic assistance—in particular, fiscal reform—has played an important role in sustaining the stability of a country at the heart of one of the world’s most volatile regions.

On paper, Jordan is a stable middle-income country with an educated population, an above-average public health system, and a strategic trading location between the Middle East and North Africa. But Jordan was deeply shaken by the Arab Spring protests of 2011 and 2012, which—according to local reporting and DAI’s firsthand observations —were motivated less by a desire for political liberalization than by impatience with the pace of socioeconomic development and the extent of socioeconomic inclusion.

The most recent poll conducted by the Center for Strategic Studies—a leading policy think tank in Amman—reveals that “economic development remained a top priority to Jordanians with 23 percent of interviewees wanting the government to ‘urgently’ address unemployment, 18 percent high living costs, and 15 percent poverty.” While the overall unemployment rate in Jordan since 2009 has fluctuated between 11 and 14 percent, about one-third of youth ages 15–24 are unemployed, according to the World Bank.

In March 2014, King Abdullah II directed his government to devise an economic blueprint to guide Jordan’s national economy for the next 10 years: “The number one priority and foremost challenge our citizens face,” he said, “is to improve their living conditions and to secure better jobs that provide them and their families with a decent living and hope for a better future.”

A Fiscal Pivot Toward Stability

Despite the delicate political and economic equilibrium that Jordan has deftly maintained since the Kingdom’s founding in 1946, economic grievances came to the fore during Jordan’s Arab Spring. Demonstrators voiced frustration over the concentration of power and resources in the hands of elites. Fears arose that perceived and actual economic inequalities, and the lack of meaningful paths to inclusion in moderate Jordanian society, could drive young people into the extremist camp, either locally or in neighboring Syria, Iraq, or Palestine.

Responding to this threat, a core group of donors has worked to restore Jordan’s political and economic equilibrium by assisting the government to strengthen its fiscal management, with the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID)’s Jordan Fiscal Reform Project II (FRP II) playing a prominent role. When FRP II was launched in 2009, it was focused on modernization of fiscal institutions, directing technical assistance to the sovereign authorities responsible for taxation and spending—specifically the Ministry of Finance and Customs Department—under the broad rubric of promoting “results-oriented government.” Implemented by DAI, FRP II quickly shifted gears to support the Government of Jordan’s economic stabilization efforts. While many of the needed reforms remained constant, the context for reform had changed, and economic stability became FRP II’s top priority.

Assisted by its international partners and advised by FRP II, the Government of Jordan developed an economic stabilization plan aimed at addressing short-term citizen grievances. The plan included concessional lending from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), bond issuances of $1.25 billion and $1 billion backed by U.S. Government guarantee, augmented direct budget support, technical assistance to fiscal institutions, and a short- and medium-term energy supply strategy to respond to gas pipeline sabotage in the Sinai Peninsula.

In turn, the Government of Jordan committed to reforms that would stabilize its medium-term fiscal outlook, and as a result, the Kingdom’s public finances saw tangible improvements: foreign-exchange reserves have recovered to more than three months of export value, stabilizing trade prospects for staple industries such as apparel, jewelry, textiles, and pharmaceuticals; sovereign borrowing has plateaued and borrowing costs have decreased—including, importantly, for domestic borrowing—thereby improving Jordan’s credit rating; and a package of economic measures including a new Investment and Income Tax Law have made it simpler for Jordanians to do business while leading to fairer, more transparent, and more effective public spending.

Tackling the Gas Crisis

Much of the fiscal stress in Jordan stemmed from the interruption of affordable natural gas imports from Egypt after pipeline bombings in Sinai. In response, the Government was forced to import gas through the Port of Aqaba at triple the price. Compounding that market spike was a price control regime that fixed the retail price of gas, so when the wholesale price shot up, the Government was forced to cover the additional costs.

FRP II brought in experts to develop with Jordanian counterparts an energy supply strategy to mitigate the damage. New sources of supply were identified, deals signed, and domestic policies changed to increase energy efficiency and gradually roll back the subsidies that were sapping the national budget. To bridge the short-term financing gap before new energy sources came online, international partners provided budget support, loan guarantees, and technical assistance. Throughout, FRP II—and the Fiscal Reform Project Bridge Activity, which launched in October 2014—have provided the critical support that Jordanian leadership needed. This enabled the Ministry of Finance, for example, to produce the National Accounts and analysis required to improve accountability and comply with IMF and USAID conditionality. A new IMF Stand-By Arrangement is currently under discussion to continue the fund’s lending and assistance to the Kingdom.

Four years after the onset of the Arab Spring, Jordan faces new challenges, including terror groups such as ISIL, growing concern about homegrown extremism—particularly in less developed cities and towns—and the influx of 1.4 million Syrian refugees, two-thirds of whom are living below the national poverty line. However, the political and economic equilibrium is holding. The Kingdom’s national security apparatus surely deserves credit for bucking the regional trend. But without fiscal reform assistance from USAID and contributions by others toward economic stability, Jordan’s 2015 would almost certainly have a considerably darker outlook.