When the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) launched the Water and Development Plan under the U.S. Global Water Strategy (2017–2022), it set an ambitious target of reaching 15 million people with sustainable drinking water services and 8 million with sustainable sanitation services.

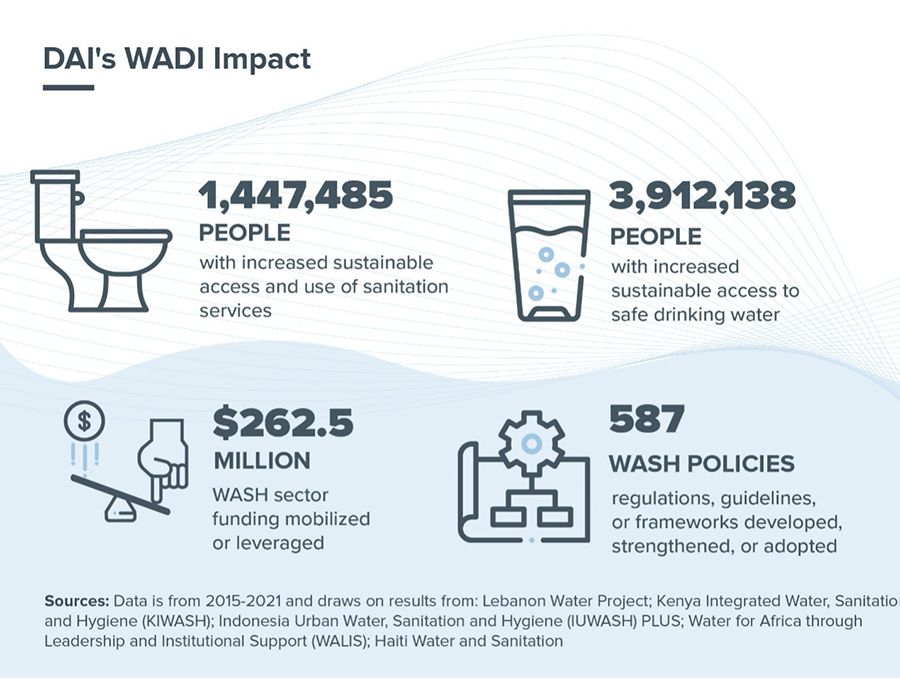

The agency designed the Water and Development (WADI) contract as an umbrella mechanism to procure activities in support of these goals. As DAI is now wrapping up WADI projects in Haiti, Indonesia, Kenya, Lebanon, and an institutional support project in Africa, we engaged an external consultant from Aguaconsult to illuminate lessons learned with the potential to inform future programs.

Lesson 1: “Software” Investments are Critical and must be Strategically Sequenced with Water “Hardware”

The water sector has largely shifted away from an infrastructure-first approach, with development partners acknowledging that interventions need to holistically address ongoing service delivery. Our projects primarily focused on technical assistance and governance-related interventions, using infrastructure investments strategically to improve service provider performance.

For example, the USAID Water and Sanitation Project in Haiti is using a data-driven utility reform model centered on the World Bank’s Utility Turnaround Framework to achieve service provision goals set by the service providers themselves. This approach came to be highly valued by local stakeholders as the utilities demonstrated significant performance gains, raising revenues as well as improving operations. Despite its initial desire to prioritize infrastructure, the Government of Haiti now sees USAID’s work as a model and is scaling up aspects of the project—such as an mWater-developed data management system—to all 28 utilities across the country.

The importance of “hardware” interventions that complement technical assistance should not be overlooked, however. Among the analyzed projects, it proved consistently important to be able to support targeted infrastructure activities—such as installing meters or repairing networks—where these hardware interventions were in turn critical to achieving service delivery goals. For example, the Kenya Integrated Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (KIWASH)project and the Lebanon Water Project (LWP) upgraded, extended, or rehabilitated existing infrastructure in ways that complement technical assistance designed to improve efficiency, reduce operating and maintenance costs, and increase resilience.

Layering “hard” and “soft” interventions within a single demonstration zone shows how these types of interventions can work in tandem to maximize impact. For example, LWP implemented infrastructure, civic engagement, water demand management, and private sector engagement interventions all in well-defined areas. Sequencing these interventions can be a challenge, however, if hardware interventions are fully dependent on other sector actors, and projects cannot deliver quick wins for service providers.

The appropriate blend of hard and soft interventions will vary, by necessity, depending on where a country is on its development journey. As countries mobilize and direct more of their internal budgets toward infrastructure and sector development, development partners can dedicate more of their budgets toward “software,” eventually moving towards graduation from traditional development aid.

All of our country-specific projects included investments in both infrastructure and technical assistance, but the proportion targeted toward hardware interventions was relatively higher in Haiti, a fragile state with large infrastructure needs, than in Indonesia, where the existing infrastructure is more expansive and the government devotes significant public resources to the water sector. In all cases, the review underscored the importance of ensuring that infrastructure is designed to support service providers in achieving performance goals and is not driven by top-down political priorities.

Lesson 2: Strong Partnerships Drive Successful Service Delivery Reform—But Take Time to Create

Across all five projects, expanded access to sustainable water security, sanitation, and hygiene (WSSH) services relied on forming strong partnerships with local sector actors. Being responsive to the needs of local partners and accountable for commitments to them are key to building these effective relationships.

Under the Water for Africa Through Leadership and Institutional Support (WALIS) project, governments developed their own requests for WALIS’s training and equipment support to build the data and monitoring systems they wanted. Working with service providers and local governments, our projects developed performance improvement plans, governance regimes, and monitoring tools to help set service delivery and management goals and co-designed the support that would help achieve them.

Partnerships with the private sector and financial institutions were equally important in driving change in the WSSH sector. LWP, for example, facilitated a partnership between the South Lebanon Water Establishment and Cash United, with the approval of the Ministry of Finance. This contract allowed for the expansion of customer points of service, online bill payment, electronic points of sale, and door-to-door bill collection service for the utility. The project acted as a trusted, neutral broker to facilitate relationships among governments, service providers, and the private sector.

To achieve these enabling partnerships, our projects embedded staff in sub-national government or utility offices. After an initially slow start in gaining traction with local partners in Kenya, KIWASH embedded staff—including service provider capacity building specialists, WSSH governance specialists, and engineers—within county government offices. Similarly, the USAID Water and Sanitation Project in Haiti and LWP embedded staff within utility offices, using government and utility protocols, staff, and reporting channels to deliver project results. In both cases, this approach meant that project staff became trusted partners who had a clear understanding of the day-to-day challenges, could tailor solutions, and were readily available to provide technical support when needed, while also strengthening local systems. It is critical that embedded staff do not displace local talent, so our projects worked to ensure that we supported and built capacity and did not directly undertake work that is best performed by government or utility staff.

WADI projects typically worked across multiple jurisdictions, where local governments and service providers have varying capacities, operated in different socio-economic contexts, and progressed at different rates. Building strong relationships allowed us to tailor support based on an intimate understanding of the different needs and opportunities presented by those contexts. These different rates of progress within a single country can also afford opportunities for peer-to-peer learning, which we found to be a valuable approach to building capacity. In some cases, utility partners were more likely to internalize lessons from their counterparts rather than from “outside” experts. For instance, KIWASH facilitated a benchmarking visit of staff from utilities in Kitui and Makueni to two of the best-performing utilities in Kenya, where the four providers collaborated to transfer strategies for nonrevenue water management.

But building valuable and durable partnerships takes time—often more time than a typical five-year project allows—and benefits from consistency in personal relationships. Once locally sustainable partnerships are established, our projects can taper their support, eventually exiting entirely.

Lesson 3: Medium and Large Commercial Partners Are Needed to Achieve Sustainable Household Sanitation at Scale

Across the household sanitation interventions, we found that focusing on training local artisans and small-scale retailers as the key actors in the sanitation market did not result in scale or sustainable businesses. This finding is in line with recent research that shows sanitation is rarely viable as a standalone, full-time business, and that the market-based sanitation interventions that scale have generally been driven by entrepreneurs adding toilets to existing, related business lines. While local masons and other small-scale actors play an important part in the sanitation value chain, medium-sized and larger businesses are often more appropriate to play the role of focal point enterprises for consumers. These businesses are better positioned with the capital, business skills, management capacity, and adjacent market experience to plan for scale from the start, and to become profitable.

The WSSH sector’s understanding of sanitation market systems has evolved since the first WADI projects were designed. Some of our projects were able to adapt their market-based sanitation approach by pivoting to engage with mid-level businesses such as hardware shops and construction materials suppliers. For example, the Indonesia Urban WASH Penyehatan Lingkungan untuk Semua (IUWASH PLUS) team worked with hardware stores that sell plumbing and construction materials and can act as one-stop shops linked to skilled builders and offering payment by installments to individual households. Both IUWASH PLUS and KIWASH successfully used community health volunteers, who received commissions for sales, to activate demand. This was a low-cost strategy for supporting sanitation market development and is likely to be sustainable because demand activation does not depend on external funds.

Even when larger-scale manufacturers are active in the sanitation market, the availability of products alone is not enough to drive widespread adoption of household sanitation. KIWASH worked with both Lixil and SilAfrica to increase sales of sanitation products, with KIWASH strengthening the enabling environment by helping public health departments to aggregate demand and facilitating savings/credit groups to offer finance. By addressing all these aspects of the market system, KIWASH enabled its target villages to achieve a dramatic increase in households having access to improved sanitation—from 3 percent to 67 percent over the life of the project.

Lesson 4: Investments in Governance and Transparency Have Tangible Returns

The water sector is known for its potential for corruption, but our projects took on the role of “honest brokers”—neutral players who can bring others together to resolve issues—in a successful effort to increase transparency and improve governance.

They began by taking a fresh look at key sector issues and players, assessing those players not only in terms of their formal mandates, but the reality of the power dynamics between them, the extent of their authority, and their real level of decentralized autonomy. We used a variety of tools to draw this picture, including political economy analysis, due diligence appraisals, strengths and weaknesses analysis, and participatory-based assessments—starting early in the projects to develop the right implementation approaches and save time in building effective partnerships. For example, KIWASH built on its knowledge of the political economy in Kenya and close relationships with county governments to improve the governance processes around utility board selection, moving away from the “chairman for life” scenario, which opens the door to undue influence and outright corruption.

One strategy we found valuable was to keep the focus on motivating progress in the sector and try to counterbalance any incentives tending toward corruption. Performance indices for service providers engaged in IUWASH PLUS and KIWASH, for example, kept stakeholders aligned around a common vision of success in WSSH service delivery. Improving accountability among the stakeholders in a system—such as between water consumers and operators or citizens and local governments—is also vital to building trust and ultimately triggering positive behaviors and incentive structures. In Kenya, KIWASH supported forums that brought together government officials, civil society, and the private sector to discuss sector progress and needs. In Kitui County, these forums are now being funded by the county government. Similarly, LWP worked to improve civic engagement by supporting utilities to increase engagement with customers, municipalities, local civil society groups, and religious leaders, including in public fora. Breaking entrenched patterns of patronage or corruption requires vision, commitment, and political will from national stakeholders.

The WALIS Improving WASH Evidence-Based Decision-Making program took a demand-driven approach to expanding smarter data use, better monitoring, greater emphasis on analysis, and evidence-based decision making. In Tanzania, WALIS worked with the Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children (MoHCDGEC) to develop a publicly accessible WASH web portal for improved data transparency. The portal has quickly become a key resource for research, planning, and informed decision making. For the first time, regional and district health officers within MOHCDGEC, research institutions, donor groups, local media, and higher learning institutions can now access this data, improving accountability and decision making.

Lesson 5: Learning and Adaptive Management are Crucial

The process of strengthening WSSH systems rarely follows a simple, linear progression. A strong focus on collaboration, learning, and adapting (CLA)—underpinned by robust monitoring and evaluation and data systems—has proven critical to understanding our progress and challenges. We learned that to be able to operate in complex environments, our projects needed to build in processes (and time) to learn, reflect, and adapt their approaches as needed.

Monitoring and learning activities, using both qualitative and quantitative data, were an important foundation across our projects. Using data beyond typical performance monitoring indicators allowed project staff to focus on meaningful outcomes that could inform intervention strategies, as the USAID Water and Sanitation project did in measuring Haiti’s utility performance against the utility turnaround framework, in addition to tracking project beneficiaries.

Under IUWASH PLUS, the project team realized that tailored strategies would be needed to reach the bottom 40 percent by wealth. Developing these strategies required deep learning about people’s motivations for investing in WSSH services, and the barriers they face. To complement a traditional formative research study using household surveys and focus group discussions, IUWASH PLUS staff added 30 hours of continuous, “live-in” observation of families as they went about their daily routines. These “homestays” provided a unique window into the lives of the urban poor and how they cope with sub-optimal access to water and sanitation facilities, shedding light on behaviors that are sometimes habitual and unconscious.

Learning and demonstration activities at the sub-national or service provider scale created entry points to catalyze national change. For example, in the USAID Water and Sanitation project, the mWater data system was developed in cooperation with the project’s partner utilities and regional authorities to meet their specific needs. Haiti’s regional and national authorities then took on the key role of sharing learning about the data system with other utilities, thereby enabling widespread adoption of the tool beyond the project sites.

Over the approximately five years that these WADI projects were active, they saw significant changes in the operating contexts. In Haiti, our project continued operating throughout widespread protests, kidnappings, the assassination of the president, and a magnitude 7.2 earthquake. The COVID-19 pandemic and resulting economic impacts affected every country in the world, putting pressure on essential services such as water and sanitation, and affecting the ability of staff to implement activities. All our projects adapted their approaches in response, as with the inclusion of new handwashing promotion activities in IUWASH PLUS and KIWASH to support infection prevention, for example, and LWP’s emphasis on reducing operating and maintenance costs to support utilities facing falling revenues.

Looking Toward the Future

The state of the WSSH sector has shifted dramatically since these projects were first conceptualized, with a growing consensus that all development actors need to think about strengthening local systems and forming strong partnerships with local actors to achieve sustainable water and sanitation solutions. Strengthening a water service provider—and the ecosystem in which it functions—should not be considered as a one-off or short-term process. Our projects work in close collaboration with local partners to ensure that they achieve sustained impacts beyond what could be achieved by directly delivering services.

Recently launched projects such as USAID’s Nepal Karnali Water Activity and the Lebanon Water, Sanitation, and Conservation (WSC) Project are already making use of these lessons in developing their approaches to sequencing infrastructure with technical assistance, building partnerships, strengthening governance, and CLA.