It’s not easy being a young job-seeker when adults tend to stereotype millennials as unreliable or entitled. El Salvador is no exception. In a 2017 opinion poll of 2,000 individuals (ages 16 to 60) conducted by the USAID Bridges to Employment project across 15 high-crime municipalities, most respondents said poor work ethic and lack of motivation are the main reasons youth cannot find jobs. One young man explained that “employers think we are lazy, do drugs, and hang out on the street all day just because we have not worked before.”

Bias against youth who live in high-crime neighborhoods is even more engrained. Employers exclude or “redline” job applicants from vulnerable communities—sometimes discarding resumes altogether—out of safety concerns for their company. In some cases, companies check young job candidates for tattoos or use lie detector tests during the interview process. “We had an 18-year old high school graduate who performed well on all of our psychometric evaluations,” said one human resources manager. “But when we sent him to the polygraph test, it came out that he had a relative involved with gangs. We did not hire him because of security concerns.” DAI and our local partners work with both employers and young job seekers to overcome this stigma.

On the Employer Side

We change employer perceptions of youth who come from high-crime areas by making the case that young people are not a risk but rather an overlooked talent pool. Many entry-level occupations across sectors benefit from young people’s creativity, enthusiasm, and willingness to learn. For example, young sales associates in retail jobs are often more adept at selling products to customers from similar demographics, as in the case of ADOC, El Salvador’s largest shoe manufacturer and distributor. “Young sales associates’ fashion knowledge and passion for our products is an asset to the company,” said an ADOC HR manager, “particularly in appealing to a young clientele.” Additionally, youth often have more flexibility to work as seasonal employees in hospitality and retail, meeting employers’ short-term hiring needs and giving them a chance to test youth for potential employment beyond the busy holiday periods.

Additionally, we work with employers to reduce redlining practices and adopt more inclusive recruitment and hiring strategies. USAID Bridges to Employment is building awareness among employers of the problems associated with polygraph tests. For example, test results are often skewed by a young person’s nervousness or by flawed questions, such as asking young people if they know anyone involved with gangs. Most individuals in high-crime communities know people in their neighborhood associated with gangs; as a result, most “fail” this question regardless of their actual affiliation with these groups. Due to our awareness-building, employers are beginning to change their approach. In some cases, HR no longer automatically eliminates youth who do not pass the polygraph, especially when candidates shine in other areas or have been vetted by a trusted local training partner.

Bridges to Employment also helps employers reduce HR challenges such as employee turnover by diversifying recruitment channels to include youth from high-crime areas. For example, Tigo—El Salvador’s largest phone, cable, and internet provider, with a workforce of 4,000—experiences high turnover of door-to-door salespersons and cable installers, especially in downtown San Salvador or other high-crime municipalities. With our assistance, Tigo re-examined the skills and experience needed for each position and updated job descriptions to reflect competencies and job tasks (such as working outdoors) rather than academic qualifications, thereby opening more opportunities to youth from high-crime municipalities.

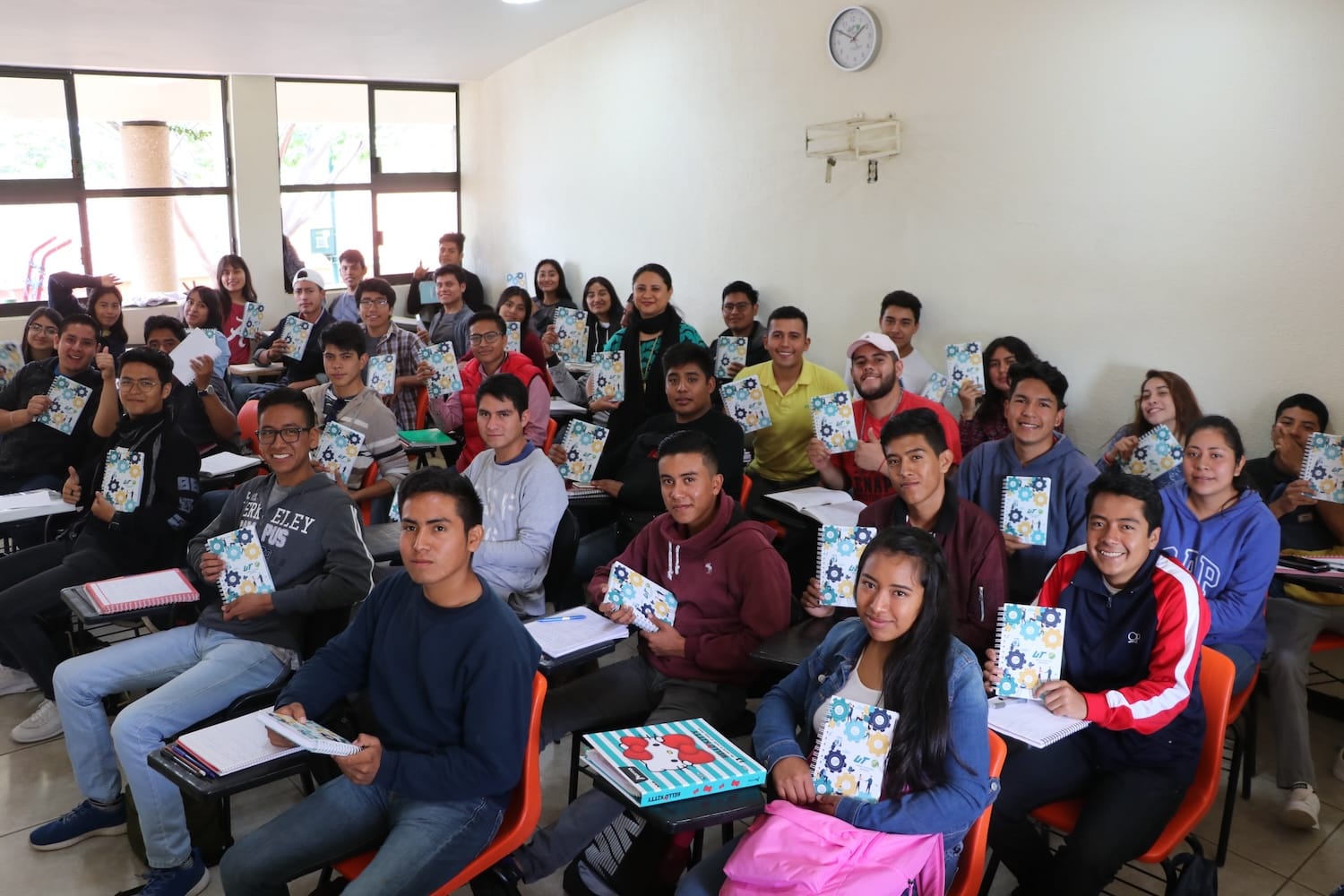

On the Youth Side

Bridges’ local training partners get inexperienced young people work-ready. Starting with the youth selection process, local workforce development partners try to pick youth based not only on their vulnerability levels but also on work motivation. Some Salvadoran youth have less economic necessity to work if their household receives remittances, for example, which can in turn influence their decisions about applying to jobs or quitting jobs they don’t like. Training center job placement managers mentor young people on the importance of building work experience as teenagers or young adults to signal to future employers their work ethic and reliability. They also manage the expectations of young people taking on entry-level jobs likely to entail low wages, occasionally difficult customers, or unpredictable schedules.

Employers are clear that life skills are critical for workplace success. USAID Bridges to Employment’s local partners deliver 64 hours of life skills training to all youth participants, covering communication, honesty, punctuality, self-confidence, conflict resolution, teamwork, and workplace professionalism. Employer partners such as ADOC and GD Group confirm that young people who complete such training are among their best employees in terms of attitude, people skills, and customer service. Queso Puebla, for example, a family-owned artisanal cheese company in Zacatecoluca, hired a Bridges graduate for a full-time sales job after she interned with the store. She learned initiative-taking as part of her life skills course and applied her training during her internship by taking it on herself to display cheeses in a more appealing way.

In this, as in so many other examples, the myth of young people’s laziness is giving way to the reality of self-starters seizing opportunities when they are available.