Welcome to our #mindthegap series where we’ll explore the multitrillion-dollar shortfall in financing for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and how to close it. In this primer, we provide a brief overview of development finance and its various components, including public, private, domestic, and international finance.

How Can We Achieve the SDGs?

As we edge closer to 2030, achieving the SDGs in the next seven years seems increasingly out of reach. Extreme poverty rose for the first time in almost two decades during COVID-19 and Russia’s war on Ukraine has increased food and fuel prices around the world, posing a challenge for our energy, food, and infrastructure goals.

Given the ambition of the SDGs, achieving them seems impossible without additional funding. But with aid budgets already stretched, how do we realistically finance these objectives?

When it comes to financing development, it has long been recognized that we need to look beyond bilateral and multilateral aid. In 2002, long before the SDGs were created, at the first International Conference on Financing for Development in Mexico, the Monterrey Consensus signaled a shift wherein developed and developing countries alike recognized their responsibilities in trade, aid, debt relief, and institution building.

In 2015, at the Third International Conference on Financing for Development, delegates developed the Addis Ababa Action Agenda—a framework for how to fund the newly developed SDGs. The Addis agenda highlighted four main financing types and three key considerations for financing the SDGs.

The agenda highlighted that all these types of financing are essential to stimulating development. Aid funding alone would be insufficient.

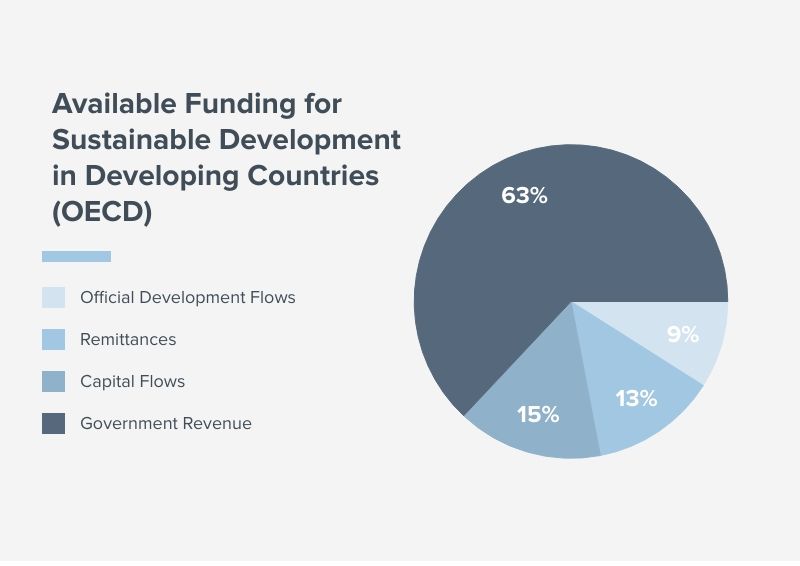

According to the OECD, overseas development assistance supplied by foreign governments accounted for just 5-10 percent of funding for sustainable development in 2019-2020, meaning that mobilizing capital in other ways was essential to achieving the goals.

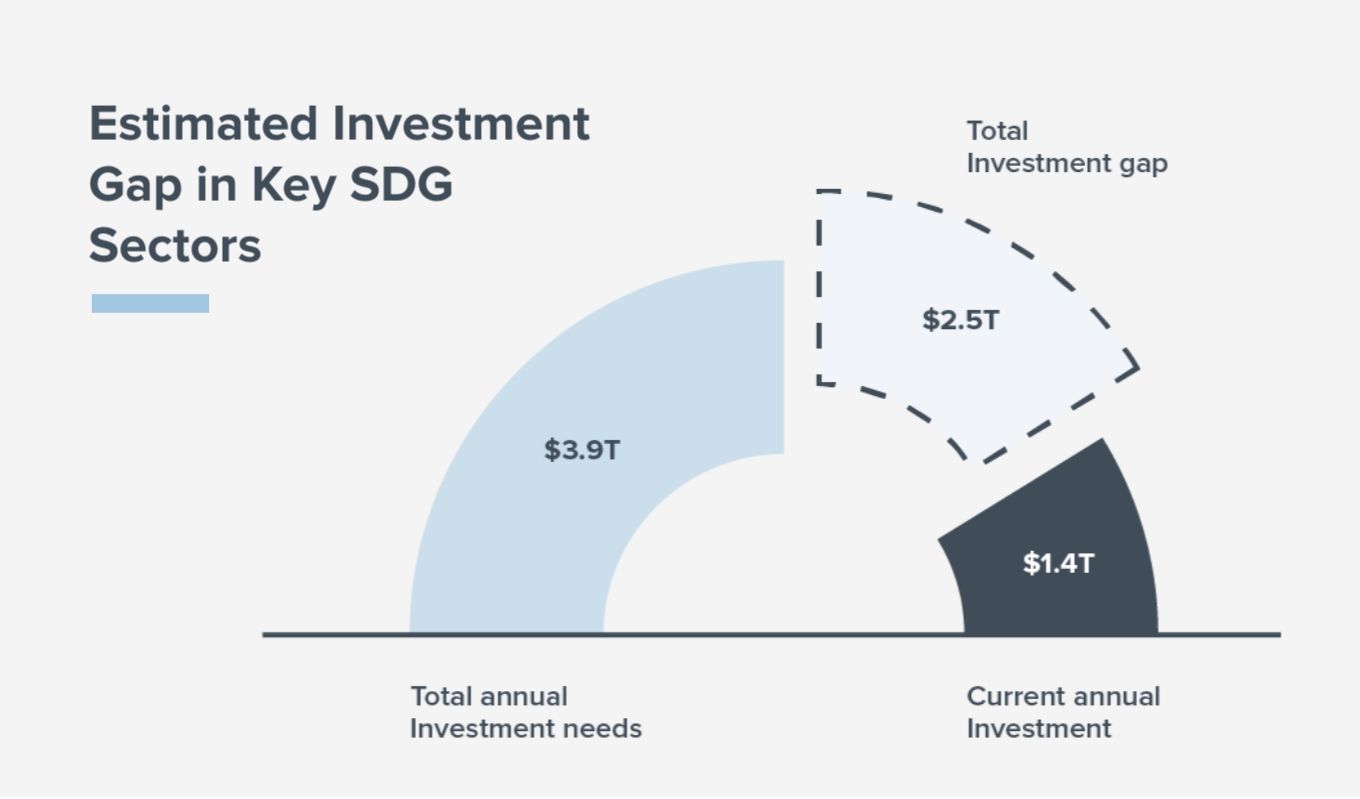

In 2016, when the goals were agreed, it was estimated some $2.5 trillion in additional capital annually was needed to achieve the SDGs. Estimating the financing gap is not an exact science and numbers vary depending on a host of variables. However, multilaterals agreed that several trillion more was needed to eradicate poverty, advance economic prosperity, and achieve the other objectives embodied in the 17 goals.

Sadly, following the advent of the pandemic in 2020, the financing gap doubled, largely due to the decrease in available domestic government revenue. Throughout the pandemic, most governments borrowed more money and were forced to spend more in response to the emergency. Coupled with a decline in foreign investment and capital flows, this dynamic ballooned the financing gap by an additional $1.4 trillion, according to the OECD.

Closing this gap will take time and will only be possible through a creative blend of financing types that maximizes the use of current development assistance and public money to strategically crowd-in more finance from the private sector. Below, we explore how different financing types can help fill the gap to reach the SDGs.

Domestic Public Finance

While bridging the financing gap will require mobilizing private finance, in reality the majority of money for development comes domestically from developing countries themselves.

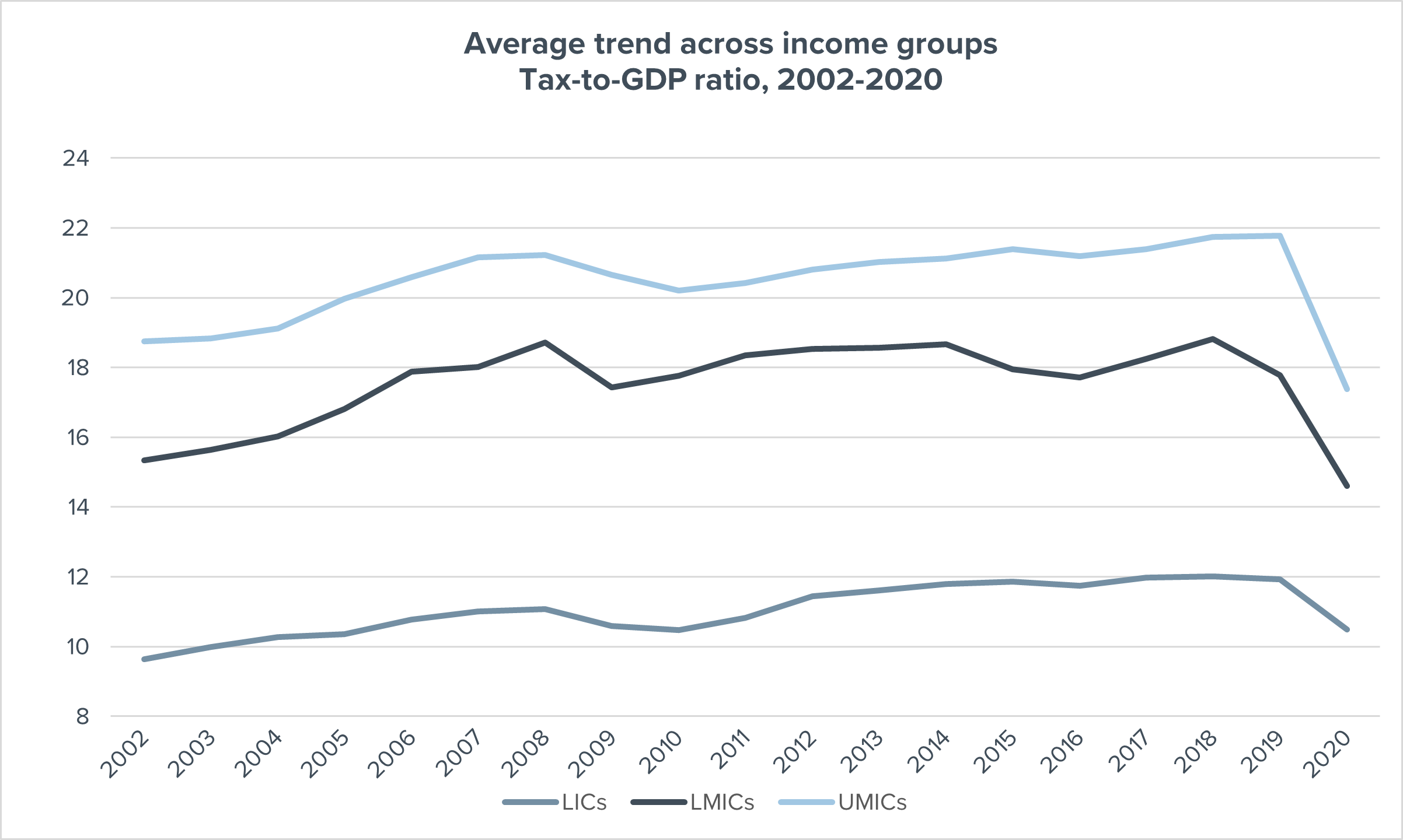

Supporting domestic public finance typically involves optimizing tax and other revenue raising while at the same time enhancing the budgeting and expenditure process. Increasing tax revenue provides countries with more resources and can boost economic growth if spent wisely on the country’s development. Appropriate tax structures also strengthen the social contract between a government and its citizens and build trust in institutions.

The World Bank recommends countries should collect at least 15 percent of their GDP in tax revenue, but most low-income countries fall below this threshold. This is often because of citizens’ low-income levels, political pressure to abstain from taxing the public, inadequate tax administration systems, or tax avoidance by larger companies.

Strengthening tax administrations by developing streamlined policies and collection systems, decreasing exemptions that undermine revenue, and enforcing broad yet fair income taxes—personal and corporate—can help raise a country’s domestic revenue.

Within the domestic public sphere, it’s also a government’s job to create an economic enabling environment for domestic and international investment. Investors are driven by risks and returns, so to attract more investors, governments need to foster a political economy that mitigates risk. That means establishing the rule of law, enforcing an effective regulatory framework, weeding out corruption, strengthening trust in institutions by fair taxation and prudent expenditure, and developing policies that support small and medium enterprise growth.

International Public Finance

Aid funding, or Official Development Assistance (ODA), is provided by governments to other countries bilaterally, or through multilateral institutions such as the United Nations or international financial institutions. The OECD defines ODA as “government aid that promotes and specifically targets the economic development and welfare of developing countries.” ODA is defined by a strict set of criteria. For example, governments seeking to quantify their ODA contributions are not allowed to claim concessional funds or non-government (that is, foundation or charity) grants and loans as ODA. ODA represents a very small percentage of money that’s available for development. In 2019, ODA represented just 3.6 percent of the total money available for development.

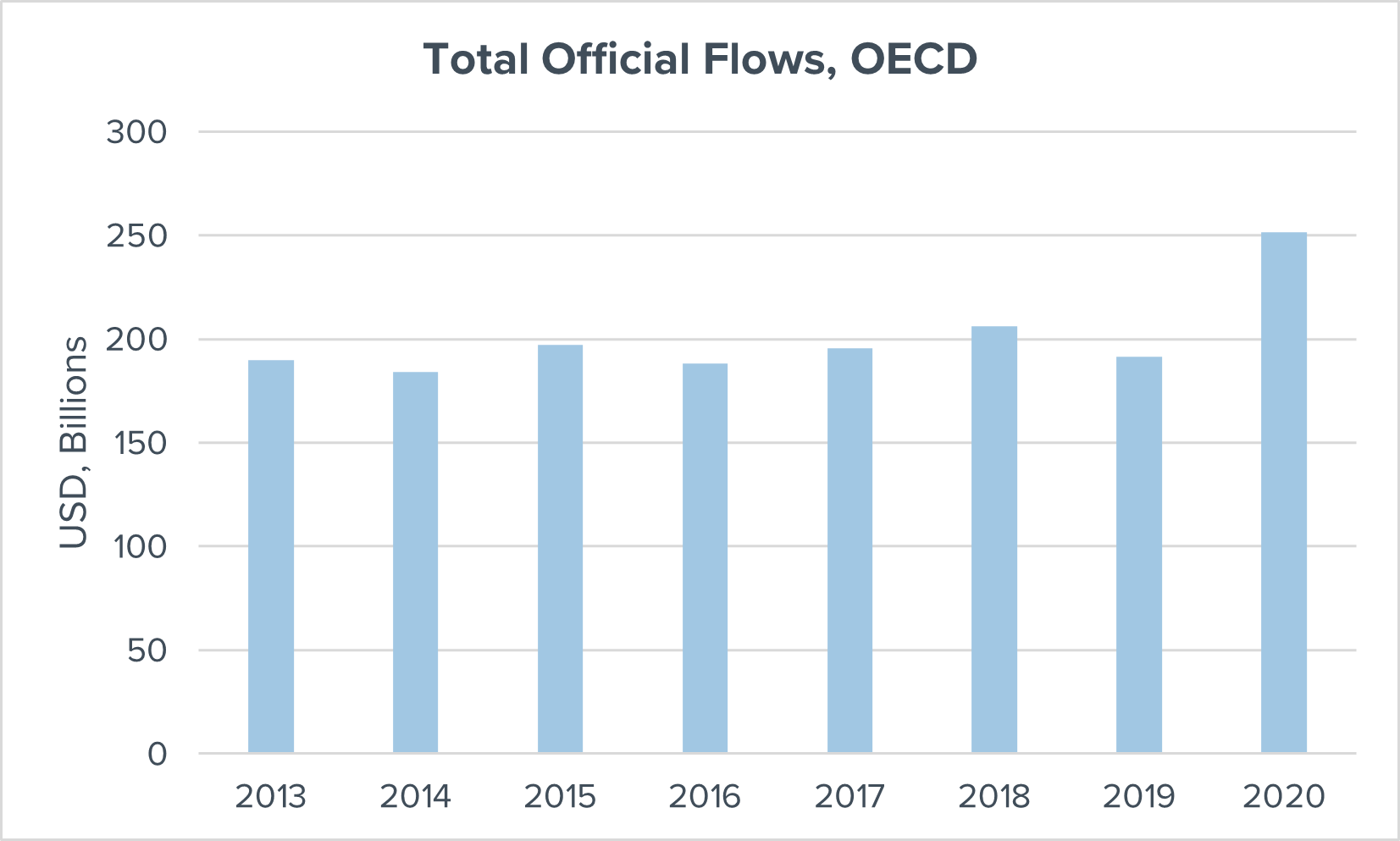

Total official flows, which count ODA and other concessionary public funds, has remained steady over the past several years, meaning they aren’t keeping pace with global inflation, nor closing the SDG financing gap.

Still, ODA will remain an important source for financing development, in part because it can catalyze other public and private finance if used strategically. ODA can de-risk private investment through co-funding, guarantees, or concessional capital, thereby enabling scarce aid money to go further, especially in middle-income countries. In low-income countries, the risk profile for private investors is higher, so finding the right projects to merge ODA and private funds is accordingly more difficult.

Domestic and International Private Finance

Private domestic and international finance are the final elements needed to help fill the SDG gap—these sources of funding include foreign and domestic direct investment and bank loans, capital markets instruments (notes, bonds, and equity), private philanthropy, and remittance flows.

Domestically—through government pension funds, investment firms, or large companies—and internationally through institutional investors, private finance has the greatest potential to drive sustainable development growth, due to the sheer scale of resources accessible through private capital markets. In 2021, global assets under management (the total market value of investments handled by investors) at the top 500 investment firms was $131 trillion. By comparison, the aid funding allocated for developing countries that year was roughly $208 billion. Put another way, just less than 3 percent of the value of assets under management would close the SDG financing gap.

For developing countries to attract private funding, prospective investments must be commercially viable, meaning investors need to have fairly strong assurances that projects will succeed, and they’ll turn a profit. The problem lies in the relatively high risk of investing in projects in developing countries. Most risks are either political—such as conflict, expropriation, government bureaucracy, or adverse business policies—or economic: foreign exchange risks, dividend repatriation, or inflation.

These risks are often beyond investors’ and investees' ability to control or manage. The public sector can play an important role in de-risking investments by providing insurance or guarantees for projects or supplying upfront “catalytic capital” to mobilize investment.

Catalytic Capital and Blended Finance

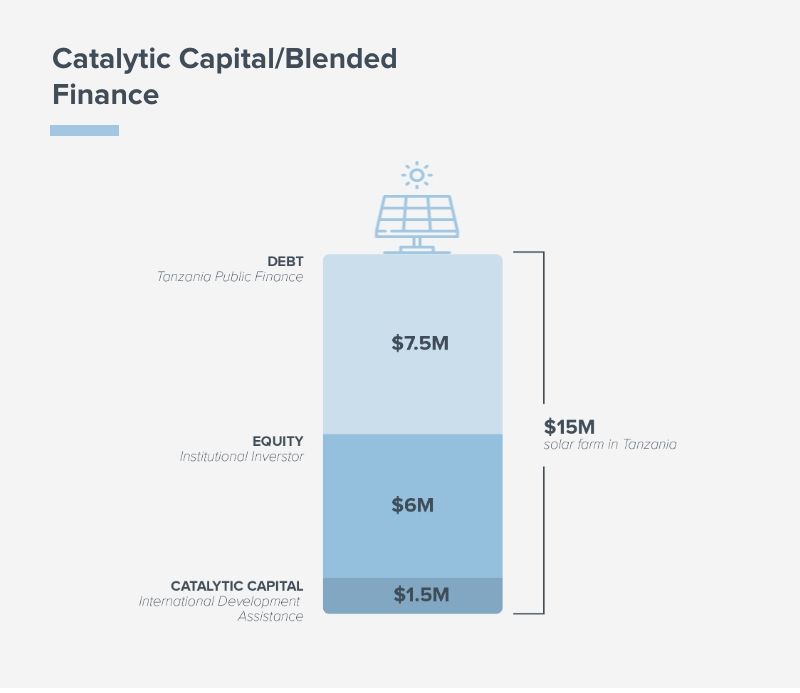

Catalytic capital is an important part of blended finance arrangements; the provider of catalytic capital accepts disproportionate risk or concessionary (reduced) returns to make it more likely that a project will generate the positive returns needed to attract private investors. It can also be used to add funds to a project to ensure it yields a positive economic, environmental, or social impact.

Catalytic capital may take several forms. It could be a grant, for example, or a low-interest loan, and it generally has three characteristics: 1) its provider bears the first losses from an investment; 2) it’s catalytic, meaning its purpose is to draw in other investors; and 3) it’s purpose-driven.

In the illustrative catalytic capital example shown, the development of a solar farm is supported through a blended financing arrangement that mixes international and domestic funds, both public and private. In this case, the government funds the majority of the project through public revenues. Bilateral development assistance of $1 million is used to attract international investors to finance the remainder of the project.

Demand-Side Development

Finally, driving investment for the SDGs isn’t just about mobilizing more financial supply; it’s also about preparing and supporting projects and companies in developing countries to become more “bankable” or “investable.”

The most common reasons given by private investors for not investing in projects with a development impact are the lack of viable projects and the cost of finding those that do exist. Donor- and government-supported efforts to introduce investors to projects and make those projects investment-ready are an important part of the overall development finance mix. For example, helping startups pitch their businesses to venture capitalists, or preparing business’ accounts and processes to receive investment, will naturally draw more investment and increase business growth.

Development finance is as broad as it is complex and requires creativity and innovation to mobilize and leverage available finance that drives growth and impact. It requires bringing the financial ecosystem together—public and private, domestic, and international—to drive the SDGs forward. In this #mindthegap series, we'll continue to explore how DAI, our clients, and our local partners are advancing this multifaceted approach.