Without good seeds, a farming family’s land, labor, and best management efforts will not reach their full potential. High-quality seeds define the genetic promise of any plant—its crop yield, its ability to tolerate pests and disease, its response to stressors such as drought, its nutritional content, and its shelf life. When farmers have improved seed varieties to work with, their farming practices—from good agronomy to soil fertility management and proper irrigation—have a greater impact. Accordingly, any economic development work in an agro-based community such as South Sudan—where approximately 85 percent of households depend on crop cultivation—must emphasize the quality of the seed supply.

Under ideal conditions, seed companies produce certified seed and sell to farmers who plant the seed, care for their crops, and eventually harvest the fruits of their labor. However, in South Sudan, the system remains immature. Private sector seed production, still in its infancy, is concentrated around major towns. Seed production in some areas has scaled down due to community conflicts and general insecurity. In remote areas, the lack of infrastructure such as road connections and telephone network coverage, and a shortage of people with technical skills, makes the business of producing, processing, packaging, and selling seed a tall order. Farmers in such areas too often rely on subpar, low-yielding varieties, perpetuating a cycle of poverty and malnutrition, and exacerbating conflict over limited food supplies.

Seed Supply as a Pathway to Resilience

In South Sudan, then, getting physical assets and inputs such as improved seeds to farmers is a serious challenge, compounded by low buying power at the community level. Some areas are only reachable by air. Local airlines charge $3 per kilogram as a transportation fee to all sites, making the cost of transportation far more than the cost of the seed itself, and removing it as a sustainable option. To illustrate, the cost of one kilogram of seed in Juba is about $2 per kilogram for groundnut and beans, $1.50 for open-pollinated maize, and $3 for sorghum. These prices raise the overall cost of seed delivery and reduce the return on investment for the smallholder farmer and any development partners assisting them. As a result, already vulnerable South Sudanese families continue to rely on cheaper, sub-par seed, leaving them vulnerable to shocks and stressors, with limited capacity to bounce back.

The Resilience through Agriculture in South Sudan (RASS) Activity, funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development, works to ensure that improved seed reaches these remote communities efficiently and cost effectively, giving farmers access to more resilient seed and elevating their ability to rebound from livelihood setbacks. South Sudan has six recognized agroecological zones—the Green Belt, the Hills and Mountains, the Flood Plains, the Ironstone Plateau, the Nile-Sobat Rivers, and the Semiarid/ Pastoral Zones—and RASS focuses on matching seed varieties to a limited set of zones at the county or state levels. A careful assessment of the local weather patterns relative to the broader agroecology and soil characteristics—and of the value chains with high potential for food, income, and nutrition—informs the seed crops RASS promotes.

Local Partnership Drives Sustainability

In many developing and post-conflict countries, farmers lack access not only to seed but to other production resources as well. Yet, communities have also demonstrated the potential to produce their own seed, reducing the production input cost. For the model to succeed, farmers must have access to high-quality early generation seed (EGS) and training in how to best cultivate, harvest, process, package, and store the seed. Initially, development partners and governments provide EGS to smallholder groups and provide the necessary instruction for seed production. As the groups grow, they are better positioned to procure their own EGS.

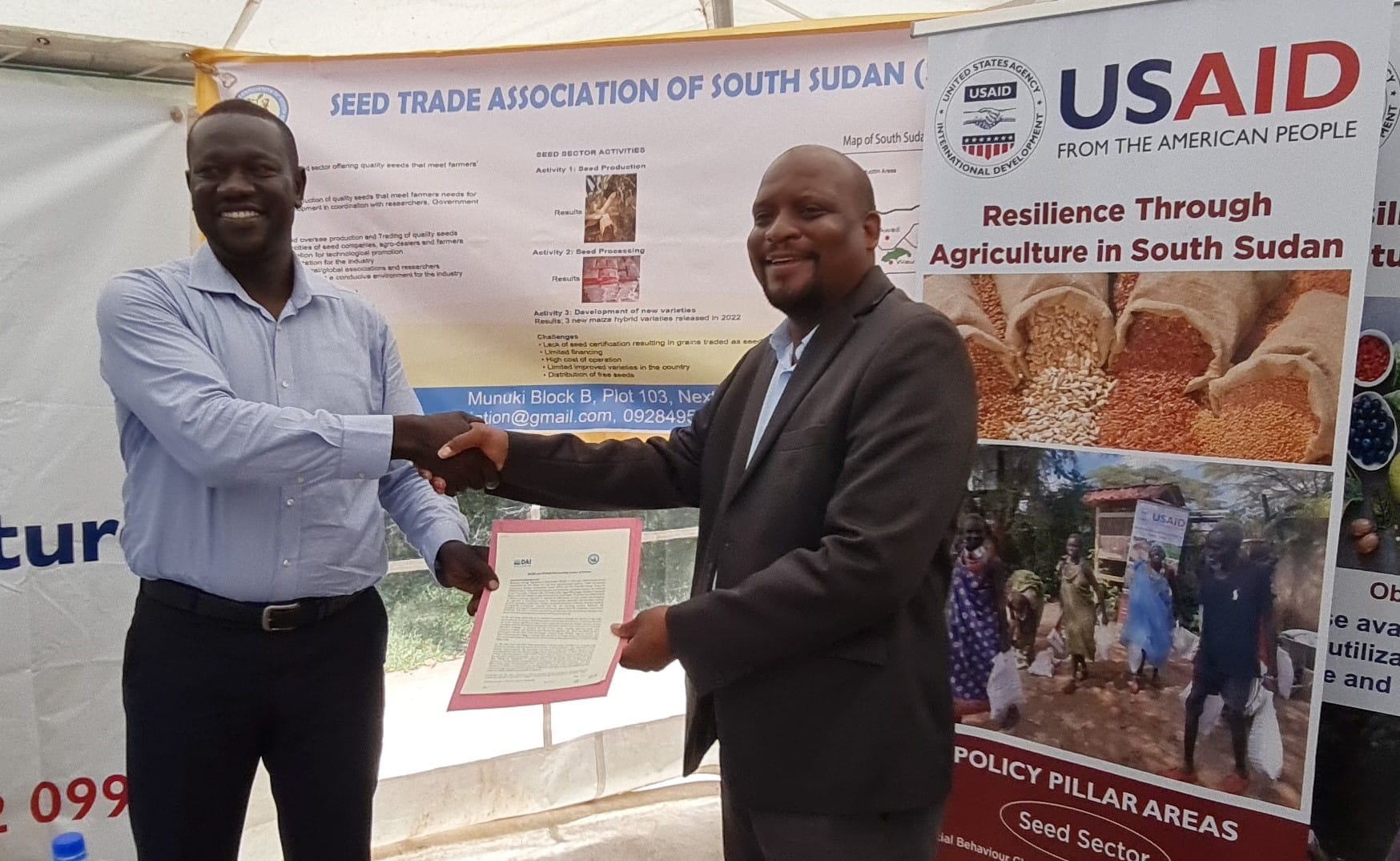

RASS is procuring EGS from companies registered in South Sudan and recognized by the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security and making the EGS available in communities for local seed production by the organized groups. This approach makes seed available where it is most needed, removes costs associated with transport and logistics, and increases the number of farmers with access to seed in the following season. For example, RASS has a partnership agreement with the Seed Traders Association of South Sudan (STASS) through which RASS leverages STASS agronomists’ expertise while at the same time building business relations between the seed production groups and seed companies.

RASS helps to form seed producer groups in its operating counties and provides them with an initial support package that includes opening up virgin land to seed production; providing training on good agricultural practices and climate-smart agriculture; supporting cultural practices around integrated weed, pest, and disease management; and verifying EGS. The groups then receive mentorship and hands-on training from the STASS agronomists to ensure they can produce high-quality seed. RASS’s customized Seed Production Training Manual builds farmers’ knowledge on land preparation, isolation distance (the recommended distance of seed fields from similar crops to avoid cross-pollination), agronomic practices, field management, and pest and disease scouting, as well as seed harvesting, processing, and packaging. STASS agronomists walk with the farmers to identify appropriate planting sites, assist with quality EGS identification of categories, determine the land needed, recommend appropriate preparation (production planning), and conduct other preliminary assessments. They also supervise planting.

The agronomists return just before flowering and stay for two weeks to train the farmers on proper removal of off-types and ensure the seed is true to type. Lastly, they return to assist with harvesting, building the seed producer groups’ capacities to recognize physiological maturity and practice proper hygiene for harvesting, threshing, processing, and packaging. In between, the RASS county-based teams work with the farmers to ensure adherence to proper production practices.

The second prong of the STASS partnership is to persuade these seed companies to set up production, processing, and selling points within the communities, using the producer groups as their outgrowers. To date, communities have produced and sold or saved for their own use 1,683 metric tons of maize, groundnut, sorghum, beans, cowpea, and other seeds. The groups have the freedom to sell their seed on the open market to any customer and have been selling within their communities, to development and humanitarian actors such as RASS, and during community seed fairs. Due to competing customers, including development and humanitarian actors, the prices at community levels are usually at par with those available in Juba. But with little to no transportation costs, improved seed is now far cheaper in the community. Therefore, in addition to making seeds available to remote communities, this work is helping develop an economic ecosystem within communities, leading to meaningful income for the producer group members and farmers, who are also reaping better harvests.

Impact of Seed at Community Level

Local seed production is affording farmers in remote South Sudan access to improved, nutritious, and climate-resilient varieties. This work builds resilience in four ways:

- Seed Matches Agroecologies. RASS is boosting the supply of climate, drought, pest, and disease-resistant/tolerant seeds tailored to the specific agroecologies at the county or state level while prioritizing specific value chains. This approach makes it more likely that farmers will still be able to bring in a harvest should a moderate drought, pest, or disease outbreak occur.

- Diversification Breeds Greater Stability. By producing seeds of different crops, farmers diversify their enterprises. If one crop should fail, there is a strong likelihood they will be able to harvest a second or third crop. For example, if maize is infested by fall armyworm, farmers are still able to harvest cowpea, bean, groundnuts, sesame, and other crops and can procure cereals from the sales of the other produce.

- Improved Incomes. Sales of improved seed bring income to the members of the seed producer groups. This gives them funds to address other necessities such as education for their children, healthcare, and more durable shelters.

- Improved Nutrition. Diverse crops support diverse diets. Farmers and their families are able to get and consume at least five food groups for a balanced diet that includes vegetables, fruits, meat, fish, milk, and eggs. Communities are also adding value through activities such as maize milling and peanut butter processing—all of which RASS is supporting, further increasing local income streams.

In South Sudan, the informal seed system remains dominant and will continue to exist alongside the developing formal system until the commercial private sector matures. RASS is contributing to this maturation process by building capacity at the community level while fostering private-sector partnerships in ways that minimize market distortions, which is key to sustainability in the improved seed business and fundamental to the resilience of remote communities.