We can bemoan the amount of finance committed to mitigate and adapt to climate change in the developing world. But the sobering truth is that even the funding we currently have in the pipeline is not getting from upstream lenders and funders to downstream users where it really matters—that is, to the small enterprises, agribusinesses, and manufacturers whose behaviors, choices, and capital investments could really make a difference to reducing greenhouse gas emissions over the coming decades.

Unlocking finance for small enterprises to access green or climate-smart technologies also supports a broader energy transition.

Part of the explanation for this blockage is that there is no single “key” that will unlock the pipeline. Rather, what multilateral development banks, development finance institutions, pension funds, and other potential financiers need is a coordinated suite of solutions that brings their capital closer to the last mile and clarifies the mutual benefits for both sides in the climate finance transaction. That is by nature a harder nut to crack, and currently, it is not happening. But our experience shows it is far from impossible.

Unlocking climate finance can help the international community limit the global temperature rise below two degrees Celsius, the target specified in the Paris Agreement. Certain economic sectors, including productive sectors, are more naturally exposed to climate shifts, be they slow-creeping changes or severe one-off shocks. In emerging economies, these same climate-vulnerable sectors—agriculture, fisheries, and tourism, for example—are crucial to inclusive economic growth and job creation. Travel and tourism alone account for 330 million jobs worldwide, and developing countries are particularly dependent on the tourism sector.

As we seek to direct green finance into those sectors, and thus protect the livelihoods of people living on the frontlines of climate vulnerability, supply is not the issue. The Climate Policy Initiative, a global think tank, estimates that in 2019 there was between $608 billion and $622 billion allocated for climate mitigation and adaptation globally, including $75 billion earmarked for developing countries (against a COP21 target of $100 billion for such countries). But that capital is not getting to users on the ground. Why not?

A major reason is that climate finance designed to flow through national financial systems to smaller financial institutions is not easily mobilised off balance sheets and toward small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Larger commercial banks are certainly looking to seize the opportunity presented as major investment banks and development finance institutions accredited by the Green Climate Fund mobilize green funding and technical assistance. And these commercial banks often seek out smaller financial institutions in local markets to syndicate this climate finance. The smaller, downstream institutions are supposed to play an important role in climate mitigation, resilience building, and adaptation efforts.

However, smaller institutions often lack the tools to appraise climate risk and tailor financial products in a way that allows them to begin lending on behalf of greener technologies or insuring against climate risk. Mispricing of climate-related physical risks can result in the knock-on effect of mispricing assets, and ultimately the misallocation of capital. The Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures, the world’s foremost initiative to address private sector contributions to climate finance, has more than 1,000 supporting organisations, including government ministries, central banks, regulators, stock exchanges, and credit-rating agencies. However, according to the Task Force’s 2019 Status Report, too few organisations are disclosing decision-useful climate-related financial information.

If these leading organisations in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries are struggling with climate-related financial information, despite being able to afford the technical support, we can imagine how challenging it can be for local financial institutions in less-developed economies to assess the climate risks in their portfolios and the credit exposure therein.

Solutions for Local Financial Institutions

Local banks are eager to finance the adoption of technologies that clear the way toward energy transition. Many businesses and communities require green technologies for productive purposes. These include both high- and low-tech solutions, ranging from solar water pumps to covering structures that protect crops from pests or extreme weather to power generation technologies such as off-grid solar systems. However, inadequate information and issues around willingness and ability to pay can all get in the way of technology adoption.

DAI’s experience in Belize sheds some light on this dynamic. In late 2020, we conducted focus groups with businesses across Belize as part of the EcoMicro Programme, funded by the Inter-American Development Bank Innovation Lab (IDB Lab) and the Government of Canada. The experience of Alex Castillo, a sugarcane producer whose name we have changed for privacy purposes, is illustrative. Under a replanting initiative designed to support farmers hit by droughts in 2016 and 2017, Castillo borrowed BZD$10,000 (approximately $5,000) from a Credit Union to help buy agricultural inputs such as high-quality seed and biofertiliser.

But yet more severe droughts in the first half of 2019 affected close to a third of his production, drastically reducing his returns. As a result, Castillo has been unable to recover from a severe climatic shock and found it harder to meet his monthly loan commitments and repay the working capital loan he took out through the replanting programme. Castillo requires a flexible financial instrument that adapts to the increasingly hostile “multi-peril” climate conditions.

Green finance products could make it possible for Castillo to purchase green or climate-smart technologies that would protect his livelihood. The first step is to help client-facing staff in financial institutions—be they loan officers or insurance claims assessors—to enhance their own climate literacy, so that they can help their customers work through the challenges of climate change.

That is easier said than done. It can be intimidating for loan officers suddenly to be expected to communicate how green technologies such as a solar system (a combination of a panel, a battery, and an inverter) works to power a customer’s machine. It takes training to begin to explain the workings of climate-smart infrastructure, such as a structure that protects crops from infestations or severe weather and allows a farmer to plant more than one crop in a season. Bank officials do not need to be technology experts, but they need to know enough to avoid miss-selling financial products. Upstream and downstream financial institutions alike must adopt longer-term thinking if they are to support the energy transition objectives of local business communities and sub-national and national governments.

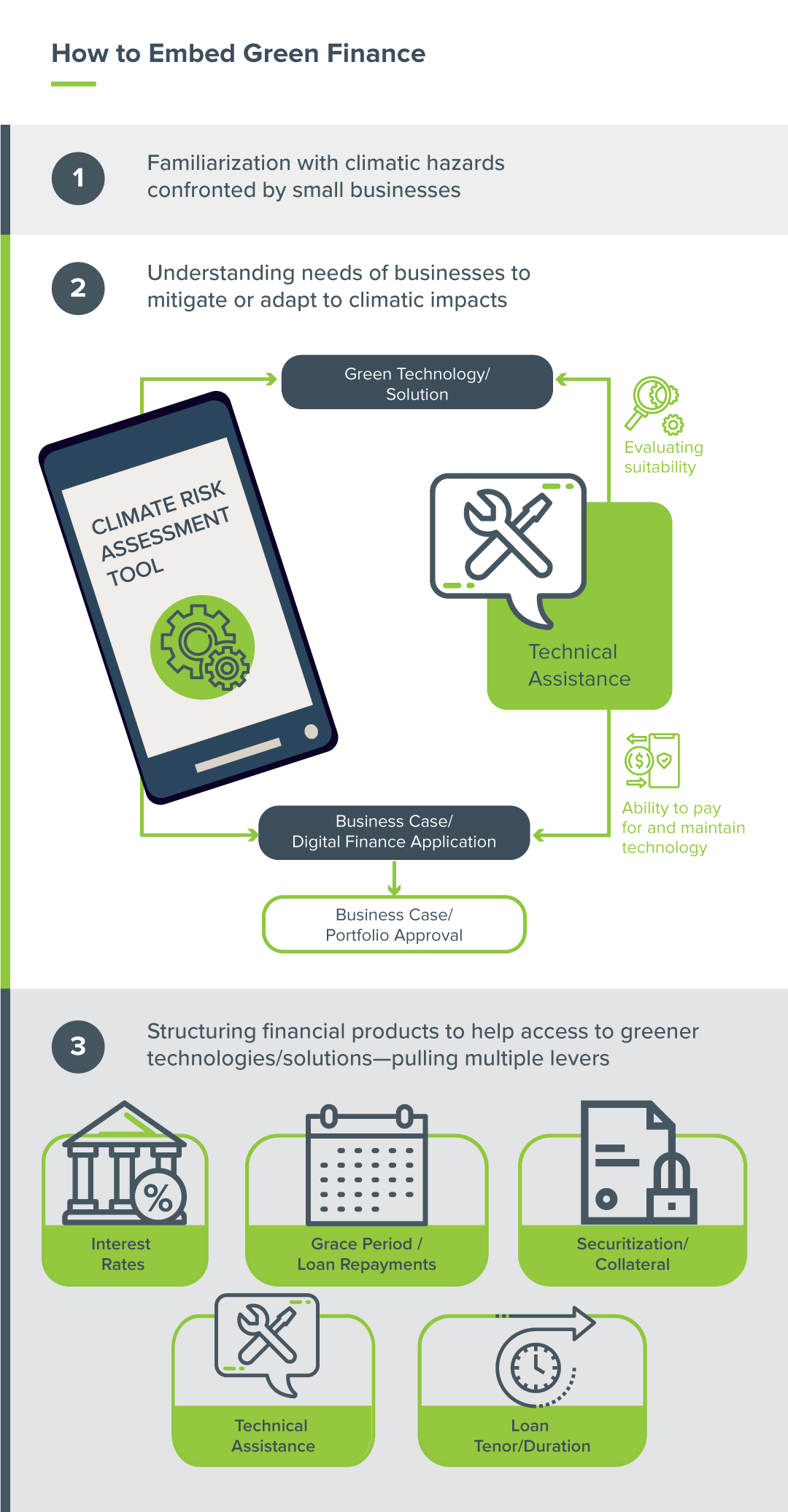

Smaller financial institutions also need help in understanding how to connect their customers to related expertise—for example, the ecosystem of installation, maintenance, and repair support firms that can orchestrate the overall solution for their customers. They will also need a climate risk tool integrated into the core financial systems they use to underwrite financial products. By enhancing the overall business case or financial portfolio approval process, the financial institutions can structure bespoke and more appropriate green financial products. Taking these products from pilot to scale will require patience and support.

Fit-for-Purpose Climate Risk Appraisal

Conducting the due diligence needed to calculate loan, insurance, or re-insurance premiums on capital-intensive green infrastructure requires a high degree of climate literacy. For major infrastructure projects, risk assessors have access to complex algorithms and artificial intelligence to compute risk scoring, and the expense and time involved is more than justified by the size of the investment at stake. However, for smaller financial institutions working with small enterprises to access technology that is less capital intensive, this high-end, time- and cost-intensive risk-assessment capability is simply not viable. They need a different, more cost-effective approach to appraise climate risk, without all the “bells and whistles,” and one that their client-facing staff can be trained to perform. In this context, a good climate risk tool should be able to assess portfolio vulnerability from three perspectives:

- Information from the client showing a robust business case for the acquisition of a green or climate-smart technology

- Geo-localised information showing the probability of a climate-related event or trend relevant to business sectors represented in the portfolio

- Information showing client businesses’ level of preparation and ability to assimilate and exploit green or climate-smart technologies.

Taking incremental steps will steadily increase the confidence of local financial institutions when it comes to “cracking the nut” of green finance for SMEs. A program of assistance to help them take these steps would include the following general principles of more inclusive product design:

- Supporting financial institutions to guide their SME customers to make their business cases credible and loan applications accurate.

- Assisting local financial institutions to transition away from paper-based applications and toward digitised processes, and optimising digital repayment where possible.

- Encouraging financiers to work with local regulatory authorities to alleviate collateral requirements and bring them within reach of smaller businesses (for example, permitting businesses to collateralise movable assets such as equipment and materials or bills of sale).

- Smoothing borrowers’ cash flow to make it easier for them to pay for financial products (for example, loan and interest repayments). For instance, the seasonality of certain commodities (such as agricultural crops) may require grace periods or freezes on the loan or interest repayment or both; the idea is to provide some flexibility on repayment when revenue generation is low (planting and growing seasons) and increase repayment as revenue spikes (harvest). The other option is to design repayment schedules around the national meteorological service-defined seasons (for example, hurricane seasons).

- Adjusting the payment mechanism to suit the business (perhaps by providing flexibility on payment frequency).

In addition to these general principles, we should take a “green” lens to our design and implementation of financial services:

- Incorporating specialist technical assistance to evaluate the needs and appropriateness of each climate-smart technology.

- Integrating climate risk appraisal and assessing the preparedness of businesses to accommodate green technologies.

- Making the duration of the product (say a loan) match the lifecycle of the green technology, so as to smooth its adoption and spread the repayment over a commensurate cycle. For example, the lifecycle of a solar system can vary between 10 and 25 years. Seeking a longer-term loan—spreading the repayment over a longer horizon—reinforces SMEs’ ability to pay for the technology.

- Working with the customs or inland revenue authorities to grant tax concessions for green technology that requires importation—this price reduction can help a technology become widely available and yield the benefits of scale.

- Building shock-responsive financial instruments to mitigate unpredictable off-seasons.

Patiently applying such a suite of solutions will begin to unblock climate finance flows for those hard-working, productive businesses so crucial to the prosperity of frontier and emerging economies.