The transition to clean energy requires massive investment from all quarters. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change made it clear that the world will never reach the goals of the Paris Agreement on climate change without major contributions from advanced and emerging economies, which currently account for around 70 percent of global emissions.

Enter, via the melee that was COP26, the Political Declaration on the Just Energy Transition in South Africa. Signed by the governments of South Africa, the United Kingdom, the United States, France, Germany, and the European Union, the Declaration outlines a partnership to support the decarbonization of South Africa’s heavily coal-dependent energy system—underwritten by financing of $8.5 billion over the next three to five years.

Such targeted support to a key producer and consumer of coal could be transformative if it is well implemented, and could emerge as a model. There are already suggestions of similar packages for countries such as India (the second largest producer of coal after China), Indonesia (the fourth largest producer of coal and Southeast Asia’s biggest gas supplier), and Kazakhstan (home to Central Asia’s largest recoverable coal reserves).

Extending such measures to developing economies where reserves of coal, oil, and gas have not yet been exploited could also be effective, but raises complex issues including energy access and the right to develop energy resources. These concerns are paramount in Sub-Saharan Africa, home to three-quarters of the global population without access to electricity. In neighboring Mozambique, for example, rich in coal and boasting the third-largest reserves of natural gas in Africa, only 32 percent of the population has reliable access to electricity, dropping to just 7 percent in rural areas.

Finding the right balance between just transition, climate change action, and equitable energy access will be critical, and the eyes of the world will be on the South African test case. In this paper, we briefly review the Declaration and the complex questions it raises, and offer some initial thoughts on how policymakers and development practitioners can address some of the challenges ahead.

Coal—The “Dirty” Fuel

The past 12 months have seen increased scrutiny of the coal sector, which currently supplies around 35 percent of global energy. Its higher carbon emissions per watt-hour, compared to other hydrocarbons, make it a primary target for replacement, particularly as cleaner alternatives become cheaper. Countries still planning long-term coal investments risk ending up with expensive stranded assets.

Mindful of this risk, many financial institutions have stepped away from funding coal projects. Even countries such as China, South Korea, and Japan, which had been filling that investment gap in many African and Asian countries, have stepped back. At the 76th session of the UN General Assembly in September 2021, President Xi Jinping announced that China “will not build new coal-fired power projects abroad.” Shortly after, the Bank of China announced it would no longer finance new coal mining and power projects abroad for the last quarter of 2021, including a new coal-fired power plant for the South African Musina-Makhado Special Economic Zone.

Granted, the final language of the Glasgow Climate Pact saw the “phase out” of coal-fired power replaced with “phase down,” but the general sentiment remains squarely anti-coal.

South Africa—A Coal Dependent Nation

For the South African government, addressing climate change is a priority, particularly its transition from coal to clean power. President Ramaphosa set up the nation’s Presidential Climate Commission to develop an energy transition framework that is fair for all. Ahead of COP26, South Africa submitted new, more ambitious climate commitments in its revised Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), underscoring the country’s commitment to reach Net Zero by 2050.

Delivering against this NDC will not be easy. The fourth largest global exporter of coal, South Africa is both fossil fuel-rich and fossil fuel-dependent. Around 80 percent of its energy needs are met by coal power and even today the country is modernizing old and inefficient power plants and infrastructure to increase output still further.

This dependence on coal is the primary reason why South Africa is the world’s 12th largest emitter of CO2 and there has been both internal and external pressure for the country to transition to cleaner energy, both for climate and health reasons (5,000 deaths a year are attributable to poor air quality linked to coal-fired power stations) and as part of a broader system upgrade (power outages are a major constraint on the country’s economic growth).

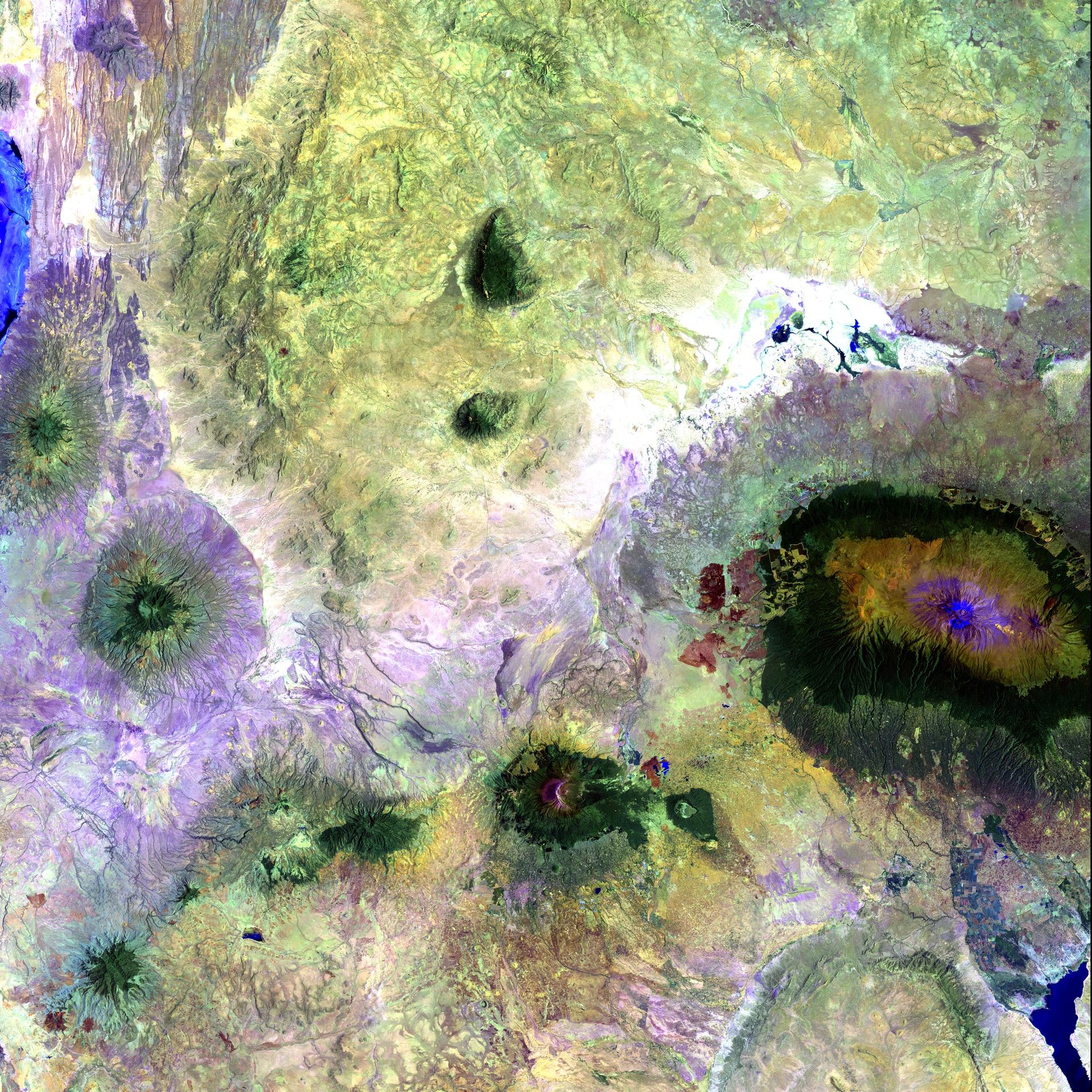

South Africa's dependence on coal makes it the 12th largest emitter of CO2. Photo: AdobeStock

The Declaration

The South African Government itself was the primary architect of the Political Declaration on the Just Energy Transition in South Africa, which aims to move the nation toward low emissions and climate-resilient development, accelerate the decarbonization of the electricity system, and develop new economic opportunities.

A “just” transition is particularly important to South Africa. It was the only country to mention justice in its first NDC, providing a chapter on “just transition” in the National Development Plan, and it has supported a series of national dialogues, assessments, and consultations on the social and economic challenges involved. To be just, the transition must ensure that a workforce dependent on the fossil-fuel sector has opportunities to retrain, and that women, youth, minorities, and marginalized groups have equal opportunity to participate; that new jobs provide a living wage, safe workplaces, and rights that are respected; and that people, particularly the poor and vulnerable, do not become collateral damage in the transition and can access affordable and clean energy.

Acknowledging South Africa’s complex economic context and the need to rapidly decarbonize while protecting the economy and livelihoods, the Declaration envisages a task force that will oversee the partnership and guide the process by:

- Supporting the jobs and skills transition.

- Managing state energy company Eskom’s debt and supporting it as an agent of change.

- Supporting local industry and supply chains to take advantage of the transition.

- Supporting technical innovation to drive further acceleration.

South Africa has relatively strong credentials in designing policies to support an inclusive energy transition. The South African Renewable Energy Technology Center, for example, provides basic safety and technical training and accredits wind turbine and PV service technicians. More than 32,000 direct jobs have been attributed to this program through 2017, and the Center estimates it will support more than 100,000 jobs over the 20-year program period. It will be interesting to see how new policies and programs will be developed under the auspices of the Declaration and its partners.

What Happens Next?

The structure of that partnership is starting to emerge. The Presidential Climate Commission has been tasked with developing a transition framework in 2022. It released an initial report in January, which includes an analysis of the coal value chain, financing options, and implications for water security in the context of climate risks. The report provides the framework to start to address issues relating to governance, economic diversification, labor market interventions, and social support.

Clarity is still required around how the Declaration will be operationalized, including who will be on the task force and how decisions will be made. Still to be fleshed out is the investment framework, agreement on how differing views of the donors and the Government of South Africa will be reconciled, and how three key strands of activity— decommissioning coal plants, supporting renewable energy, and transitioning skills and jobs—will be prioritized.

Other challenges to be addressed include:

- Supporting coal-dependent and vulnerable regions and sectors: The country already suffers from unemployment and, while transitioning jobs from coal to renewables sounds ideal, many of these jobs will not be accessible to workers leaving coal production—the skills required in the renewables sector are not the same.

- Transparency and ownership: South Africa must increase efforts to ensure the transparency of the transition process and step up inclusive social dialogue around it.

- Equity in decision making: Women and under-represented communities need to be included in decision making and in job creation activities.

- Local value creation: The disruptions caused by COVID-19 highlighted the importance of domestic value chains. Strengthening these will present local job opportunities that should also promote social justice in both racial and gender terms. South Africa has recently discovered substantial gas reserves that might be used as a bridging fuel, which would support the national economy and align with a lower carbon trajectory but would not support Net Zero. How will natural gas feature in the transition strategy?

- Additional finance: Eskom estimates the transition from coal will cost $27 billion, three times more than the amount to be facilitated via the Declaration. Will there be other funding sources (public and especially private) that will bridge this gap without adding debt?

The Way Forward

The successful rollout of the Declaration in South Africa is contingent on the partner countries’ delivery of the funding. South Africa is the biggest and most important economy in the Southern African Development Community region and is capable of leveraging significant funds. In our view, there are five areas that South Africa and the partners need to implement, that will provide the governance structure and help mobilize further public and private finance:

- Define a transition financing plan with sectorial investment needs and packages relevant to the context of South Africa’s highly constrained fiscal situation.

- Establish a realistic plan to resolve Eskom’s problems, including unbundling the company to its principal components—generation, transmission, and distribution—and encourage fair and transparent private sector participation in the energy sector. The Government has recently approved amendments to the Electricity Regulation Act, which will create a competitive market for electricity generation and allow an independent state-owned transmission company to be established.

- Focus on the expansion and modernization of the grid and allow private sector participation and financing.

- Develop and finance plans for the retirement, relocation, and retraining of workers, with a focus on women and vulnerable groups.

- Develop mechanisms for stakeholder consultations and engagement, with transparency around reporting progress.

Transitioning to a green economy while leaving no one behind is a multidimensional challenge involving governance, job creation, education, health, social protection, and other imperatives. As we confront the global problem of climate change, we need good examples of what works at the country level. We have much to learn from the South Africa partnership and how investments of this nature can help to deliver just transitions at scale.