Government spending worldwide represents, on average, 34 percent of gross domestic product per year—or a third of the world’s economy. The risk of mismanaging government funds or utilizing public institutions for private gain is high, and is more pronounced in countries characterized by weak institutions or susceptible to fragility or conflict. Sadly, efforts to tackle corruption are often sensitive, politicized, or unsustainable, and explicit “anti-corruption efforts” frequently jeopardize political buy-in for reform.

The punitive approach to anti-corruption—characterized by crackdowns on corrupt practices through investigation, prosecution, and sanctions of corrupt individuals—though sometimes successful, can also be highly dependent on the rule of law and well-functioning institutions, which are commonly part of the same “systemic corruption” equation. Experience shows that in seeking to address the mismanagement of public funds, a punitive approach should be complemented by a political and institutional commitment to change systems and underlying attitudes.

A public financial management (PFM) approach to corruption—largely understood as a function of government accountability, transparency, and appropriate levels of discretion—is well-positioned to advance anti-corruption efforts. While government accountability and transparency depend to a significant degree on the systemic processes and frameworks adopted by public institutions, discretionary power can distort anti-corruption efforts since it depends on public officials’ personal conduct and judgment. By optimizing the processes and systems used to manage public finances to reduce undue discretion—while promoting accountability, transparency, and citizen oversight—the PFM approach can reduce institutional vulnerabilities, opportunities for corrupt behavior, and the misuse of public funds.

Indeed, strengthening core PFM institutions can permeate the entire public sector, and the combined effects of measures such as enhanced internal controls and safeguards, internal accountability and oversight mechanisms, and social audits can encourage broad behavioral change. Importantly, the PFM approach can focus on both the supply and demand sides of governance: on the supply side, by strengthening PFM institutions, processes, and systems; on the demand side, by enhancing civil society’s capacity to engage and exert effective oversight.

Through its partnership with bilateral aid organizations—such as the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), the European Union, and the U.K. Foreign, Commonwealth, & Development Office (FCDO)—DAI has implemented dozens of projects applying the PFM approach. In this article, we describe the four pillars of that approach—prevention, detection, deterrence, and behavior change—and offer lessons learned from a body of practice that employs proactive rather than punitive methods and situates governance strengthening and anti-corruption programming as mutually reinforcing efforts.

Prevention: Stopping Corruption Before It Takes Hold

PFM processes and systems reduce undue discretion in the collection, allocation, and use of public resources. This is possible through the standardization, optimization, automation, and interoperability of processes related to national planning, budget formulation and execution, public procurement, tax collection, and customs management. Through strengthening these systems, governments can reduce opportunities for corruption, mitigating risks and vulnerability points. Sample DAI-implemented PFM initiatives include:

- Supporting Guatemala’s Tax and Customs Administration to optimize and automate the taxpayer registration process, thus reducing face-to-face interactions and undue discretion, by integrating registration, update, and cancellation processes into a digital taxpayer registry.

- Supporting the Liberia Revenue Authority (LRA) to design and launch a mobile payment solution for tax and non-tax payments covering more than

50 taxes and fees charged by the LRA and other agencies, leading to faster

certification, lower administration costs, and reduced scope for fraud and

corruption relative to cash payment methods. - Facilitating Kosovo’s Ministry of Finance, Labor, and Transfers to introduce an innovative online Invoice Tracking System, enabling both government and businesses to track the status of government payments to

suppliers of goods and services. This crucial development allows for

transparent and accountable payment management, thus reinforcing financial

integrity in one of the riskiest areas for fraud and corruption. - Assisting El Salvador’s Internal Revenue Agency to digitally transform the case management selection system (CSMS) for risk-based selection and execution of tax audits. The new e-case management solution reduces discretion in audit case selection and makes automatic case assignments to tax auditors who undertake tax audits through standardized processes and documented procedures. The CSMS provides traceability and accountability, improving the quality of decision making and reducing opportunities for corruption.

- Improving border control and management at Jordan’s Customs Department by integrating border agencies into one streamlined process while upgrading the automated system through enhanced electronic single-window capabilities, thus facilitating trade while combating fraud and illegal trafficking across thousands of declarations processed each day.

Detection: Finding Corruption Fast

PFM processes and systems can also play a substantial role in detecting irregularities in the management of public funds through mechanisms such as internal and external audits, expenditure tracking, red flag systems, and external oversight by supreme audit institutions and civil society. New technologies that help automate and digitize control processes are revolutionizing audit functions, leading to continuous transaction auditing in real time with reliability that exceeds traditional manual audit practices. Citizens can also exert effective oversight, such as monitoring large government infrastructure contracts through social audits, journalism, and media, which help expose and curb corruption. Sample DAI-implemented initiatives include:

- Helping set up an anti-fraud unit in Kosovo’s National Audit Office (NAO), which has led to significant strides in fraud detection, enabling NAO to uncover and submit 322 fraud cases for prosecution. A red flag system integrated into Kosovo’s e-procurement system flags irregular activity and 30 corruption risks in government contracting, from planning to implementation.

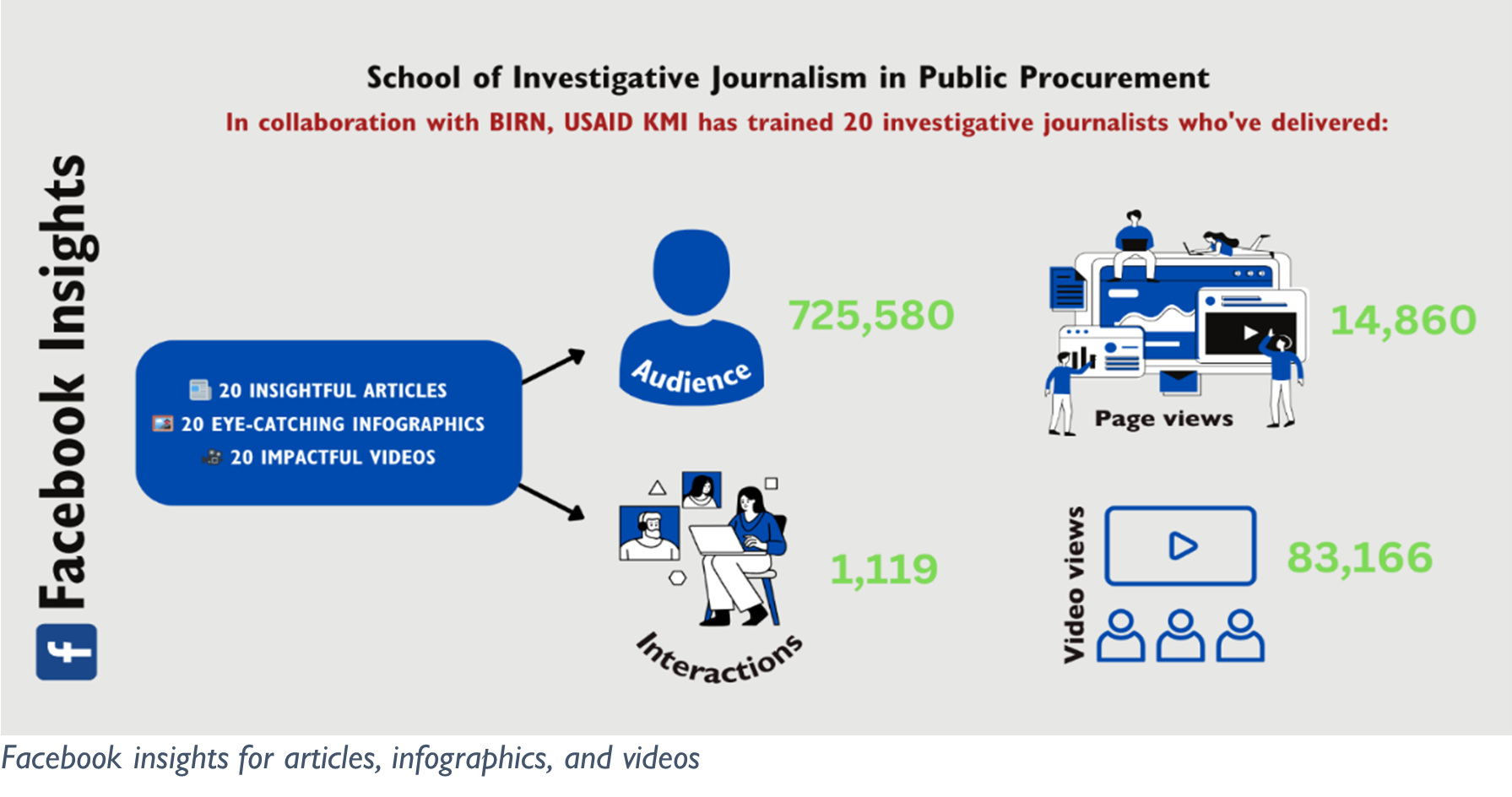

- Supporting a school of investigative journalism in Kosovo, whose reporters have collectively generated 60 products including infographics, articles, and videos that expose public procurement irregularities (and best practices) based on published government contracts.

- Assisting El Salvador’s Supreme Audit Institution to curb corruption and increase accountability in the use of public funds by launching a “Fiscal Fraud Crackdown Program” that identifies fraud risks and selects cases for investigation. Utilizing improved audit techniques, the program detected approximately $21 million in mismanaged public funds, a six-fold increase in detection from previous years.

Deterrence: Raising the Risk of Detection

Promoting internal safeguards and controls in PFM systems while enhancing fiscal transparency and citizen oversight can help deter unethical behavior by increasing the risks of detection. DAI works with government counterparts to promote greater citizen engagement across the budget cycle, improve compliance with access-to-information regulations, and develop user-friendly fiscal transparency mechanisms. Because transparency alone seldom serves as an adequate deterrent, DAI also equips civil society with the tools, knowledge, and platforms to utilize this public information to hold public officials accountable. Sample DAI-implemented initiatives include:

- Supporting 10 state governments in Nigeria to provide public access to information on the public budget formulation process and spending execution, thus increasing transparency around budget management while deterring waste and misuse of public funds.

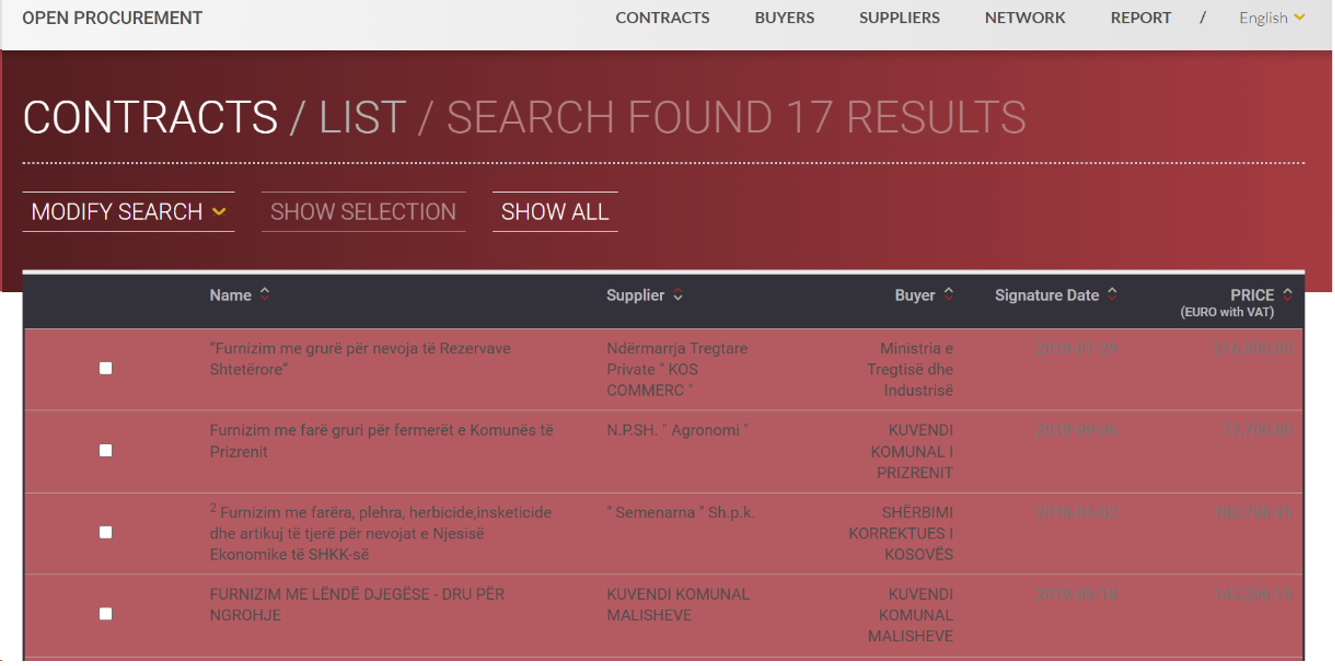

- Helping launch Kosovo’s Open Procurement Transparency Portal, providing a user-friendly platform that automatically aggregates data from the government’s e-procurement system in real time, enabling detailed analysis of financial and institutional procurement activities and government contracts. As a result, focus institutions have increased government contract reporting from 61 to 93 percent, crucial in enhancing anti-corruption measures and fostering public trust.

- Enhancing anti-corruption mechanisms in Guatemala’s Tax and Customs Administration by improving the application of Anti-Bribery Standards ISO 37001 in tax service centers and addressing identified corruption risks and loopholes in core tax administration processes.

- Working with Guatemala’s government, civil society, and international organizations through the Open Government Partnership Initiative to co-create a National Open Data Policy that enhances citizens’ rights to access public information and makes data publicly available.

- Supporting Colombia’s civil society through the “Colombia Participa” network and conducting social oversight over health and education services in 34 municipalities. The network, led by eight regional bodies encompassing 58 grassroots organizations, has improved the accountability of local investment projects in rural communities. (Watch this Facebook video about the network.)

Behavioral Change: Spreading the Word

Prevention, detection, and deterrence mechanisms encourage new patterns of behavior among government officials and citizens by increasing the perception of risk, encouraging collaborative processes, and improving controls on unethical behavior. PFM programming and systems-strengthening efforts also contribute to behavioral change and can further ensure integrity by advancing the professionalization of PFM functions and promoting ethical standards, including transparency and accountability. Sample DAI-implemented initiatives include:

- Implementing Kosovo’s Online Invoice Tracking System has led to significant achievements. For example, project-supported government institutions attained an 81 percent rate of timely invoice payments (payment within 30 days), compared to a 69 percent average in other Kosovo municipalities. Timely payment practices demonstrate a shift toward financial responsibility and transparency, reducing opportunities for corrupt activities such as payments delayed in exchange for bribes or favors, thus building trust with private companies while setting a standard of integrity and accountability in PFM.

- Embedding a culture of honesty, transparency, and integrity across government counterparts in Guatemala by supporting anti-corruption and integrity training for officials involved in budget planning and execution, public procurement, and tax collection; providing recommendations for enhancing ethics and integrity policies; and expanding the application of the ISO 37001 anti-bribery standards in tax centers.

- Integrating change management activities in reform initiatives involving technological upgrades—with the finance ministries of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Jordan—by aligning people’s capacities with the optimized processes and upgraded technology, thus reducing resistance to change and promoting buy-in for reform. Change management activities have contributed to changing mindsets and sustainable adoption of reform efforts, including highly sensitive anti-corruption initiatives.

Lessons Learned

DAI’s experience with implementing the PFM approach to tackling corruption yields the following lessons:

- Appropriately frame anti-corruption initiatives: In sensitive environments, avoid explicit labeling of anti-corruption efforts that can jeopardize political buy-in and technical progress. Instead, emphasize the technical and operational impact of the activities in terms of accountability, transparency, efficiency, and integrity, and conceive the initiative as part of a broader thinking and working politically approach.

- Support both demand and supply sides: Whenever possible, interventions should include government counterparts and civil society, which should lead to mutually reinforcing mechanisms; for example, launching fiscal transparency portals and training civil society groups to utilize the associated public data for monitoring and oversight.

- Take advantage of established accountability mechanisms: Existing accountability mechanisms such as the Open Government Partnership Initiative are effective venues for collaboration between government and civil society to promote transparency, accountability, and anti-corruption innovations.

- Complement PFM with change management approaches: Providing training in—and promoting—change management approaches are critical for the success and sustainability of PFM reforms. Harmonizing people, processes, and technology initiatives is crucial, especially when attempting to change mindsets and entrenched behavior.

- Prioritize a PFM workstream in anti-corruption strategies: A PFM workstream—including in budget management, public procurement, treasury and accounting operations, internal and external audit, tax administration, open data, and crosscutting technological innovation—should be central to any anti-corruption strategy. PFM interventions improve cross-sectoral management of public funds and can permeate the entire public sector, thus optimizing returns on investment of reform efforts.