In this second article in the series, I look at grant-making for private sector actors, using the Strengthening Host and Refugees Populations in Ethiopia (SHARPE) program as a case study. The project, funded by the U.K. Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office, offers an interesting opportunity to explore this topic given the sheer number and variety of grants provided and the challenging operating environment.

When the study was conducted, SHARPE had provided grants to more than 100 enterprises, ranging significantly in size, sophistication, and ownership-type. Broadly, these enterprises fell into three categories:

Large, national companies, often headquartered in Addis Ababa, such as Shayashone, an Addis-based agro-input supplier with a network of more than 450 vendors and 400 youth resellers across Ethiopia, and Shabelle Bank, the largest bank in the Somali region and one of the leading providers of digital financial services in Ethiopia.

Small and medium-sized local companies, typically owned by entrepreneurs in the host community, such as Shifo, a small, host-owned agro-vet based in Kebribeyah town in the Somali region, serving approximately 3,000 people in the host and refugee community.

Micro-enterprises, typically refugee-owned but also host-owned, and often informal. This category includes small-scale poultry and vegetable farmers.

How Were the Grants Used?

In general, the purpose of the grants was to catalyze the integration of host and refugee communities into high-potential supply/value chains. For medium and large companies, this meant using grants to incentivize firms to expand into host and refugee markets and “test the water.” The idea was to buy down risk for these first-mover companies. For refugee-owned micr-enterprises, grants were used to support enterprises to reach a size and sophistication where they could participate effectively in wider supply chains. Given their low income levels and difficulty accessing finance, grants to refugee businesses were generally used to provide a substantial part of the necessary financing. Mid-sized enterprises were also supported to grow and to link large companies more effectively with refugees in the capital or regional centers.

Interestingly, SHARPE grants have included cost-shares for assets such as buildings or equipment. For example, SHARPE shared the construction costs of satellite branches in refugee camps by Shabelle Bank. This approach contrasts with the guidance provided by market systems development programs such as KATALYST in Bangladesh and PRISMA in Indonesia. The PRISMA Deal Making Guidelines, for example, state that funding equipment or infrastructure should be avoided “as this can give unfair advantages to a firm and reduce the potential for replication.”

During the study, SHARPE staff explained that, given the very different and challenging context, it was important to be able to cost-share infrastructure and hardware if that is what is required to catalyze the desired innovation. We also found evidence that where companies like Shabelle Bank had invested in infrastructure in refugee markets, they were more likely to sustain their commitment to these markets post-grant.

Does the Size of the Grant and the Cost-Share Vary?

Reflecting the diversity of the enterprises supported, the grants provided by SHARPE varied significantly in value, from less than £100 to more than £200,000. The largest single subsidy was for the Somali Microfinance Institute (now Shabelle Bank), worth £222,000 (covering two different interventions). The smallest subsidy was £81, given to various refugee vegetable farmers in Gambella. There was also a large variation in the percentage cost-share provided by SHARPE, from 35 percent to 88 percent (based on the commitments set out in the grant agreements).

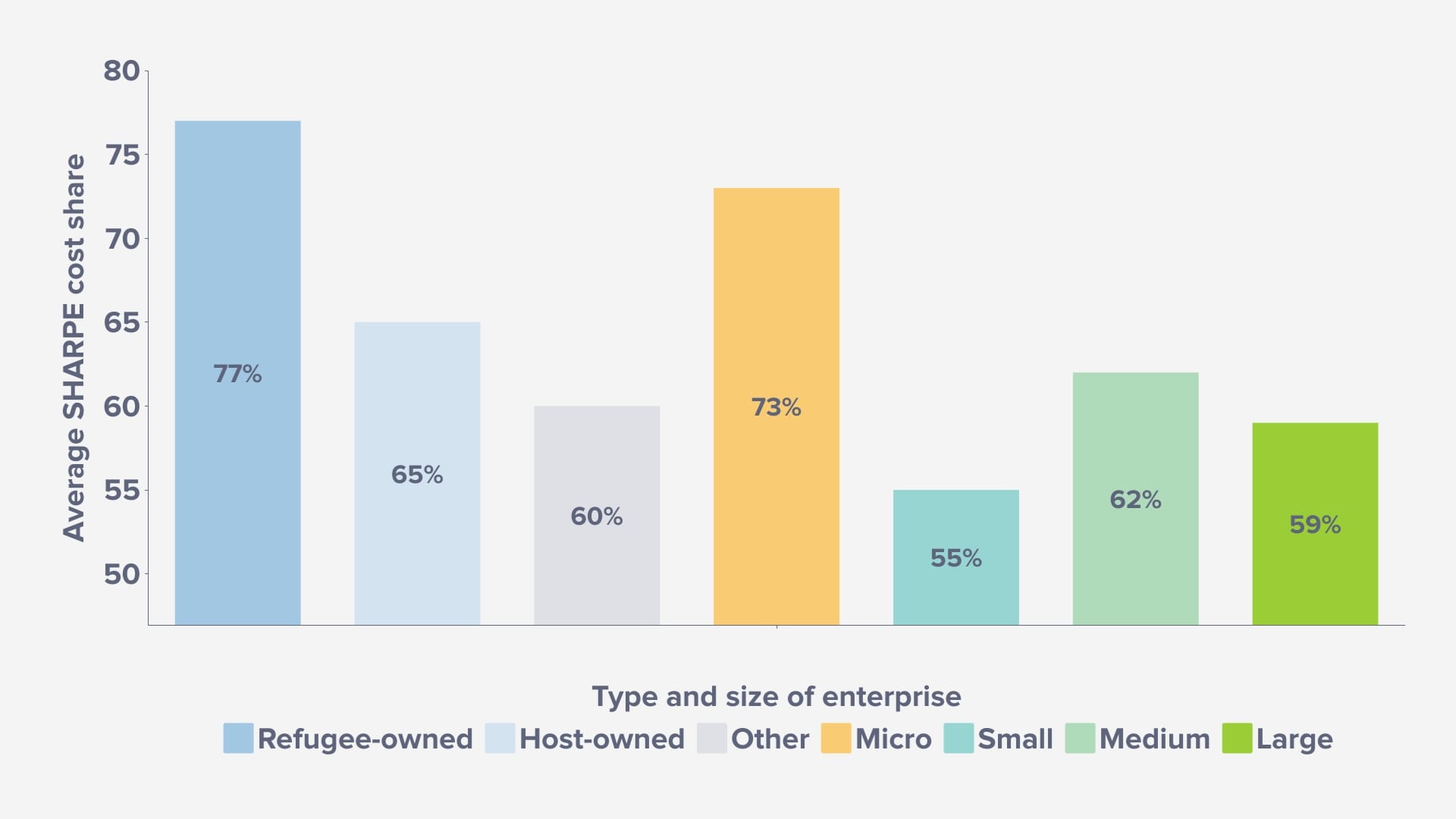

In the first article in the series, we made various predictions about how the cost-share might vary depending on the type of enterprise. In general, we found that the cost-shares provided by SHARPE matched these theoretical predictions. For example, the average SHARPE cost-share for refugee-owned businesses was 77 percent, followed by host-owned businesses at 65 percent, then “other” businesses at 60 percent. Given that refugee-owned enterprises, followed by host-owned enterprises, are least likely to be able to access internal or external finance to fund investments, this is consistent with the conceptual model. The cost-share also falls as the size of the enterprise increases, although with an anomaly for “small’ enterprises: the average cost share for microenterprises was 73 percent, falling to 59 percent for large enterprises—also consistent with the model.

For the study, we also hoped to benchmark the cost-shares provided by SHARPE with other programs operating in various contexts. Unfortunately, we could not find much publicly available data on cost-shares. However, anecdotal evidence suggests that the SHARPE cost-shares are generally higher than other private sector development programs but not other programs operating in Ethiopia. Again, this is consistent with the external literature given that SHARPE operates in regions characterized as both “thin markets” and “donor-heavy” contexts.

Do High-Cost Shares Lead to Unsustainable Outcomes?

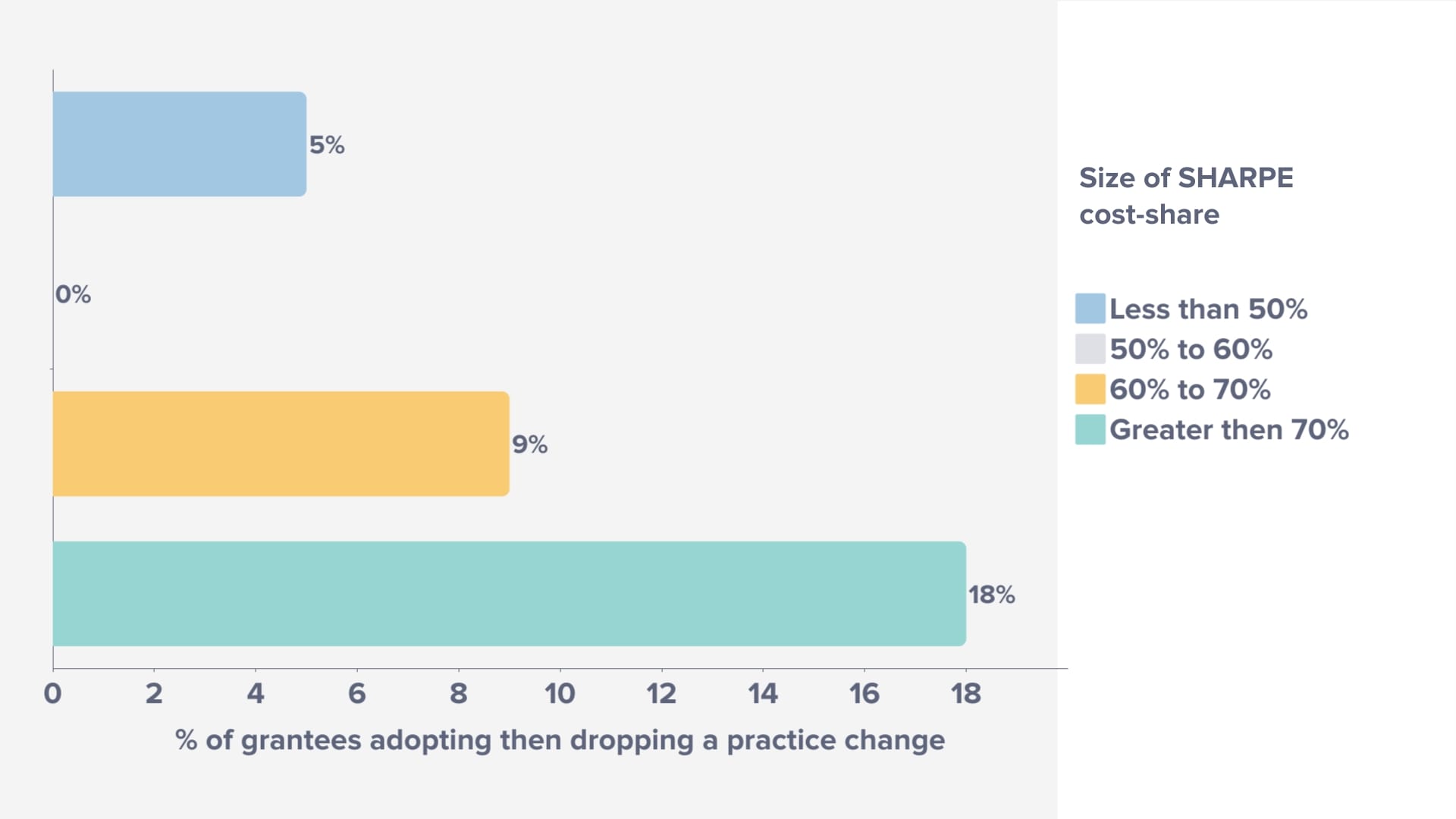

One of the reasons practitioners give for not providing high cost-shares is that they increase the risk that the recipient company is simply “in it for the money” and will not sustain the innovation or practice change beyond the end of the grant. By combining data from the SHARPE grant tracker with data from the monitoring system, we could analyze how the rate of adopting and sustaining practice changes varied across the portfolio. As shown in the graph below, the data does suggest that grantees receiving a high cost-share are more likely to adopt then drop a practice change: where the cost-share was less than 50 percent, only 5 percent of grantees adopted then dropped a practice change, versus 18 percent of grantees where the cost-share was greater than 70 percent.

If the analysis is repeated for medium and large enterprises only, two-thirds of the grantees receiving a cost-share of 70 percent or more adopted then dropped the practice change. Although many contextual factors are at play, this early evidence suggests that programs should indeed remain cautious about providing high cost-shares when providing grants to larger firms in particular.

In the third and final article in the series, I will summarize some of the key lessons and recommendations from the study.