I was recently tasked with producing a study for the Strengthening Host and Refugees Populations in Ethiopia (SHARPE) program in Ethiopia. SHARPE, funded by the U.K. Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO), works at the intersection of market systems development (MSD) and humanitarian relief, and the aim of the study was to examine how it is using grants to catalyze change and innovation among private sector actors.

The program has worked with many such actors, from refugee-owned vegetable producers to large banks and national agro-input companies. But although cost-shares, risk guarantees, and other financial instruments are key tools in the MSD facilitation toolbox, it became clear during a broader literature review that there is relatively little guidance for practitioners around grant-making. For example: When negotiating the cost-share, what is a reasonable split, and how might this vary depending on the market actor and the context?

This three-article series shares some of the lessons and insights from SHARPE, beginning with the “theory” of grant making. The second article examines the realities of grant making, using SHARPE as a case study. The third summarizes the key lessons learned and recommendations arising from the study.

Pinning Down the Concept of Grant Making

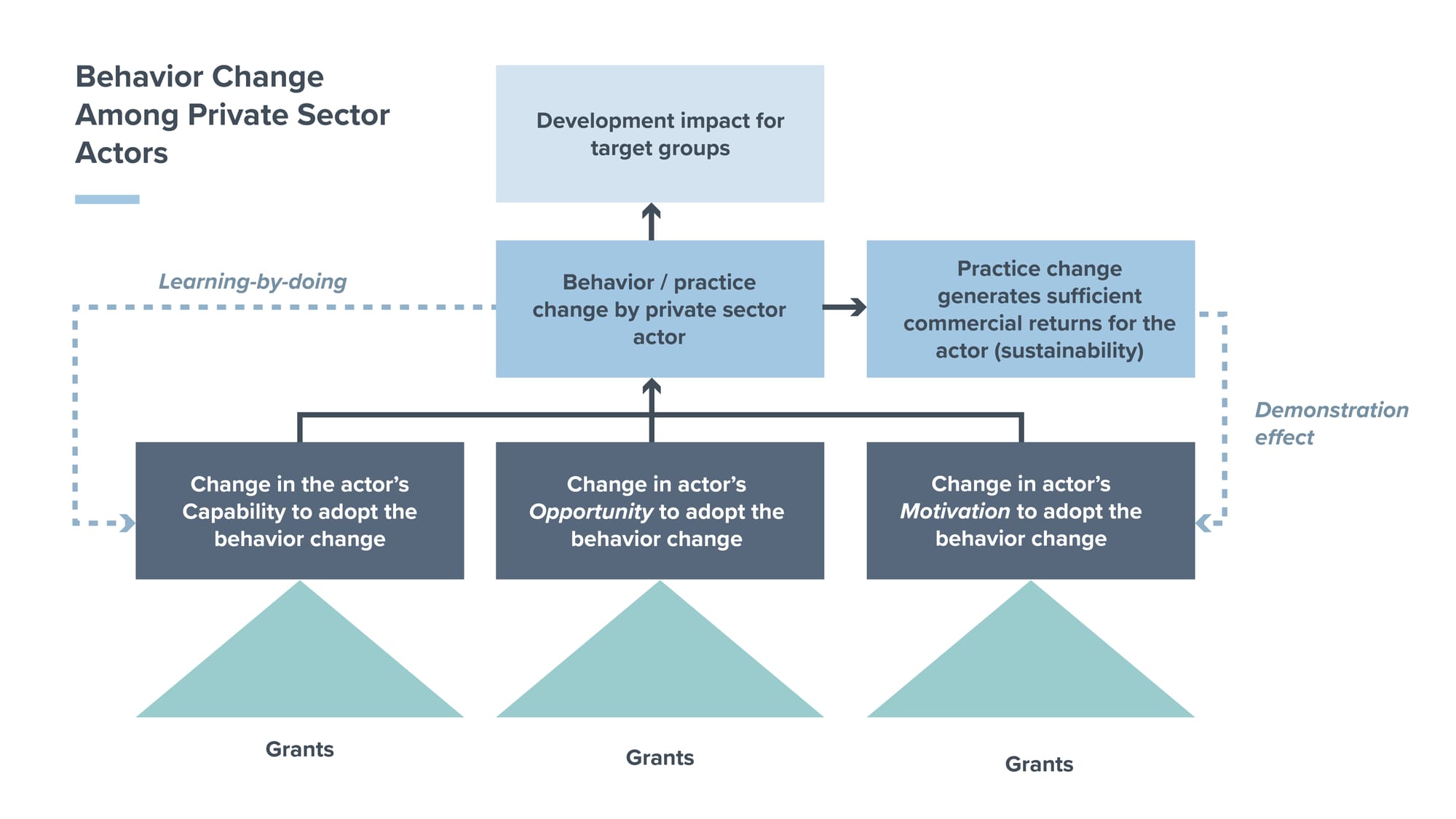

Before diving into the messy realities of making grants, we took a step back and developed a conceptual model to help us think about when grant making will be most effective (versus or in combination with non-financial instruments such as technical assistance). We also used the model to consider the factors that might determine the size of the grant or cost-share.

Following the COM-B model of behavior change, the practices and behaviors of private sector actors are driven by three factors:

- Capabilities—the actor’s knowledge, skills, and abilities.

- Opportunities—external factors that make adopting a given set of practices possible or viable.

- Motivations—the actor’s short- and long-term goals, appetite for risk, and other decision-making processes (including biases and beliefs).

Grants can bring about practice change through two mechanisms. First, cost-sharing and risk guarantees can be used to change actors’ motivations to adopt a particular practice change. For example, where a potential practice change is considered too high-risk by the actor or has unknown or untested returns, grants can be used to buy down risk, thereby removing motivational blockers of change, at least temporarily. For grants to lead to a permanent shift in an actor’s motivations, the practice change—once adopted—must generate a sufficient commercial return. This “demonstration effect” can also change the motivations of other actors, leading to wider “crowding-in” and broader adoption of the new practices.

Second, in the context of constrained sources of finance, grants can change the opportunity for private sector actors to adopt a given change by providing the necessary financial resources.

Grants are not the most direct way to address capability blockers of change, which are more directly addressed by technical assistance. However, financial instruments may lead to indirect or second-order changes in an actor’s capabilities, for example, through “learning by doing.”

What Does “Minimum Necessary” Look Like?

FCDO guidance on public subsidy programs emphasizes that they should provide the smallest cost-share necessary to catalyze the desired practice change. But what does “minimum necessary” look like? Using the model above, we identified three sets of factors:

Other Considerations

Beyond the conceptual model, two other contextual factors are evident in the literature, reflecting the reality that agreeing on the size of the cost-share is a negotiation between the company and the program. First, companies are likely to have more negotiating power in “thin” markets where the choice of partners may be limited. Second, in “donor-heavy” markets, a program may need to offer a larger grant than would otherwise be the case, especially if companies are used to receiving generous grants with minimal cost-share requirements from other donor programs.

In the second article in the series, we test this conceptual model against SHARPE’s experience in Ethiopia.