Young role models such as Malala, Amanda Gorman, and Greta Thunberg have given the world a glimmer of hope—that perhaps the world will be better one day because of their efforts. But what does it take to harness such youthful energy? What does it take to ensure we build hope and resilience, even in the face of growing unemployment, corrupt leadership, and the climate emergency? Specifically, for a country like Tanzania, bulging with a growing youth population, what will it take to unlock opportunities for young people to become drivers of an economy that needs resourceful, innovative individuals?

I do not have all the answers, but I will tell you with confidence who does—young people themselves. That is why whatever development efforts we employ in Tanzania must place young people at the center of this nation to drive decisions and lead with action.

Seventy percent of Tanzanians live in rural areas and rely on agriculture, and roughly half of Tanzania’s 60 million people is under the age of 35. In fact, the average age of a Tanzanian is just 17. To develop Tanzania’s economy therefore requires stimulating rural economies and working closely with young people. In its Vision 2025, the Government of Tanzania recognizes this priority and the need to create a “strong and competitive economy.” In alignment with this priority, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) has invested in Tanzanian agribusiness, focusing on rural people’s ability to increase agricultural production, mechanize operations, and expand market opportunities through Feed the Future, the U.S. Government’s initiative to stimulate and secure food systems.

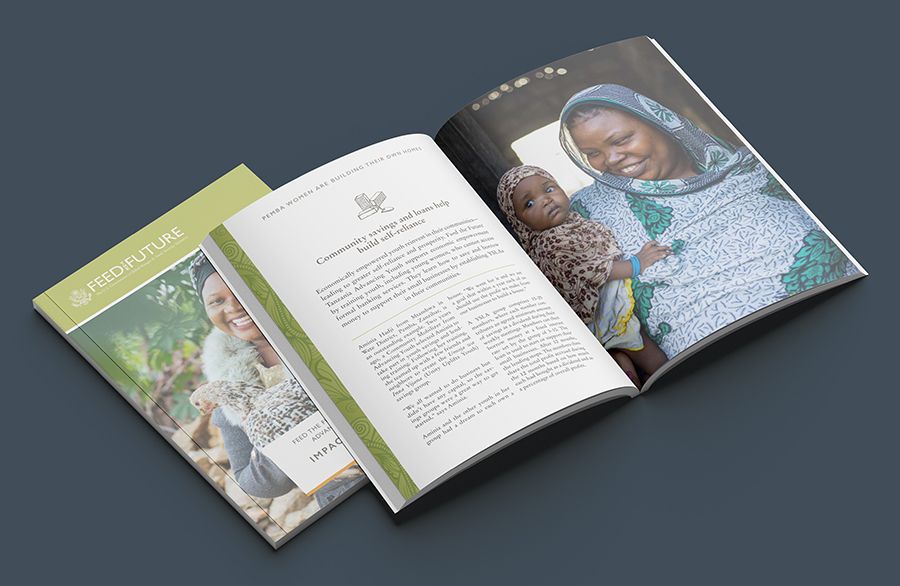

Although several Feed the Future projects already had targets to work with young people, USAID saw a need for a concerted initiative to empower youth. So, in 2017, the Feed the Future Tanzania Advancing Youth Activity was born.

Advancing Youth leveraged existing Feed the Future investments in horticulture and cereal value chains to ensure that young people in Iringa, Mbeya, and Zanzibar connect to agribusiness opportunities by gaining either employment or entrepreneurship opportunities. In addition, Advancing Youth equipped them to make better decisions about their futures through leadership training, life skills instruction, and improved access to health services.

Beyond Training

Advancing Youth also prided itself on being a “beyond training” project, recognizing that while foundational skills are important, the real challenge young people face has more to do with systemic barriers that new skills alone cannot surmount. In fact, the assumption that educated young people have the prerequisite skills to compete in the job market is typically false. They need ongoing re-skilling of soft skills and hard skills through experiential training, internships, and apprenticeships, where they experience more vivid, exemplary, and hands-on problem solving. What Advancing Youth has been able to uncover with our beyond training model is that many essential skills—such as lateral thinking, growth mindsets, conflict mediation, parenting, nutrition awareness, critical decision making, and leadership—are not taught in Tanzanian classrooms. We also learned that young Tanzanians need vocational skills in food processing and modern agriculture if they are to be valuable as employees in agricultural value chains.

These insights, along with others that informed our approach, come from a foundational youth and gender assessment and labor market survey conducted prior to implementing the program.

The youth assessment, for example, informed us that, in general, citizens, aged 15-19 and young women, in particular, have a harder time accessing programs like ours. We also learned that young women are less mobile (only traveling a 5-kilometer radius from home) than young men (who will travel up to 25 kilometers from home), which means the types of businesses, access to markets, and profits they will accrue from their efforts are affected. Unsurprisingly, young men earn higher prices for their produce and tap more opportunities than young women.

We also confirmed what I already knew as a Tanzanian woman myself: that because of restrictive traditions, young women cannot inherit land, and are raised to be seen and not heard. The latter norm limits young women’s ability to negotiate better life outcomes for themselves, in their families and communities, on issues ranging from practicing safe sex, having control of income they have toiled for, accessing technology tools, and participating in decision making. We also found that Iringa, Mbeya, and Zanzibar, like many rural settings, see more young women become mothers before age 24, most of them as single moms.

The youth and gender assessment informed our hands-on implementation approaches, motivating our efforts to debunk misconceptions about gender and the notion that working with young people is somehow difficult. Most important, the assessment led us to collaborate with local authorities to create as many opportunities as possible for young people to demonstrate what they can do. Because nothing is as clear as action, and when young people’s energy is applied in productive ways, the demonstration effect is phenomenal.

The labor and market survey, which was geared toward learning what the agribusiness industry needs, taught us that the private sector needed to be incentivized to hire young people. We resolved to do so through providing paid apprenticeships and internships at minimal costs to companies. We also learned that horticulture and poultry are high-priority value chains for youth to engage in because the products involved typically take a shorter time to generate and bring to market. Young people see entrepreneurship as a clearer path to prosperity, but unlike their forebears, they want to use modern farming methods and prefer to add value to the produce themselves, rather than leaving that process to other market players.

Unfortunately, we also learned that industry players generally lack trust in young people, assuming them to be lazy and quick results-driven, and this attitude constrains opportunities for youth. Such misconceptions explain why Advancing Youth employs the USAID Positive Youth Development framework, which advocates that youth are worthy of trust but need skills, opportunities, and resources if they are to prosper—and in turn bring prosperity to Tanzania.

What Worked

So, what did we do that worked? In sum, very simple solutions. First, in response to our youth and gender assessment, we created prescriptive gender selection measures, ensuring that 60 percent of the young people we selected for activities were female, because in this context parity alone does not foster equity. Additionally, 60 percent of all youth selected to take part in our program had to be under the age of 24, because while it is hard to reach them, they are the most in need.

Second, we worked with local and private sector partners as grantees. We trained young people in soft skills, then followed up with vocational skills. But the real game changer was creating youth savings and lending associations (YSLAs), and getting them registered to gather youth savings and disburse loans. The young people involved are not forced to establish group businesses, but we created a space where they could readily access funding through the YSLAs to start or improve businesses. Each grantee was also provided with a clear mandate to give startup capital or startup kits to young people, because helping them to get a business going required more than skills and often capital is the great impediment to getting a business off the ground. Then we followed up with mentorship and coaching. Market exposure was the next pillar—getting young people in front of buyers and potential buyers through deal rooms and trips to conduct their own market surveys and exhibitions. Some young people also received digital training to help sell their products online. Other activities included referring young people to trader associations, private companies, and other players.

As a result of these activities, many young people have grown their businesses exponentially. To take just one example, Mkami Tetere, a 25-year-old mother of two, now packages and sells ginger, tea masala, and other cooking spices under her own brand, Mkami Products. She also supplies more than two tons of rice per week to a Dar es Salaam buyer. In addition, she produces batik fabric and accessories.

After much success in her own business, Tetere co-founded a consulting firm called Five Star with several other project participants to impart the skills they received to others. They have now graduated to being grantees, receiving $50,000 from our project to roll out a similar approach and support others to create food-processing businesses. Five Star has secured contracts from CARE International, the Government of Tanzania, and the Tanzania Chamber of Commerce and Industry.

Arguably the most impactful aspect of the project has been infusing funding into youth-led business. While most financial institutions are apprehensive about trusting young people with money, Advancing Youth has modeled success in this arena. A great example is Hadija Jabir. In 2017, Jabir was a 27-year-old running an agribusiness called GBRI, exporting fresh horticultural goods to Europe. While the business had been slowly growing, GBRI saw rapid success after receiving scale-up funding of $98,000 from our project. GBRI was able to hire 250 young people, expand its production and packing operations, and launch Agriedo, an agribusiness consulting firm.

In Zanzibar, Pili Kashinje started out with one small shop. After receiving horticulture training through Feed the Future Mboga na Matunda, a horticulture value chain initiative, Kashinje started producing sweet potatoes. Later, she received entrepreneurship training and access to a YSLA that provided financing to start processing and packaging sweet potato flour. Advancing Youth then supported her to access more markets and she now supplies flour to nine schools. Kashinje recently bought a truck to transport the flour and built a small factory that employs 15 young people.

Through cases like these, the project found YSLAs to be ideal sources of alternative funding for youth-owned businesses. The magic behind them is that they are organizations built on trust, where self-selected individuals come together to save, lend, and reap the dividends of their association. The second part of the success is that the interest rates are accessible—ranging from 3 to 10 percent, compared to 18 to 50 percent that banks offer. Advancing Youth created 312 YSLAs, made up of 5,370 young people, who are collectively worth 2.4 billion Tanzanian shillings. The return rates achieved are approximately 87 percent, once again illustrating that young people can be trusted by financial institutions (especially when they have demonstrable records of borrowing and repayment).

Taking the Reins of Leadership

Beyond the work world, Advancing Youth also helped young people gain leadership skills, leading community development efforts where young people raised 130,000,000 Tanzanian shillings to build or renovate nine clinics and six schools. These efforts helped shape the perspectives of young people as change agents and capable individuals who can provide critical support to transform the communities in which they live.

As a result of Advancing Youth’s leadership training, 2,000 young people are now part of decision-making bodies at the local government level, in the private sector, and at national institutions, signaling an important shift toward intergenerational partnerships. Some 264 young people were encouraged to vie for political leadership roles during the recent local government elections, 88 of whom were elected—a tremendous vindication of Advancing Youth’s vision.

Skills for Life

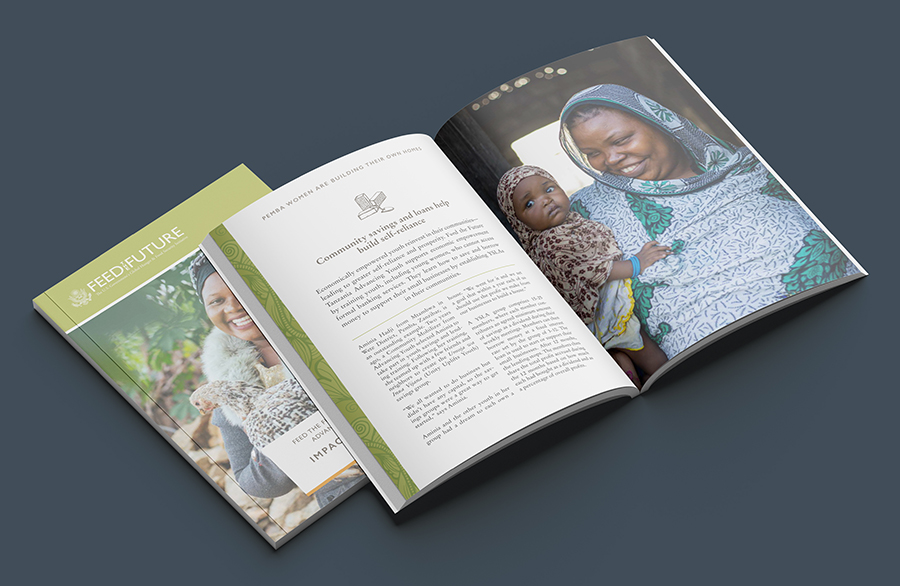

The final pillar of our activities was life skills training. Like any other group of people, the young do not have uniform experiences. A 19-year-old mother’s needs differ from those of a 29-year-old man, and our life skills training and approaches varied accordingly, with some skills training being conducted in schools, for example, but also a separate program for mothers under 24. The young mothers’ curriculum includes skills that help them raise and provide proper nutrition for their children, take leadership roles in their communities, and negotiate better outcomes for themselves and their families.

What made our young mothers’ program particularly effective was its combination of assistance in healthy living with a focus on planning and economic and leadership skills. But to make our approach work, we had to recognize the practical challenges young mothers face. For example, we offered childcare allowances so young mothers could free their time for participation in the training. At first, providing this allowance was seen as almost a revolutionary act, but once our partners saw it in action, they immediately recognized it as a pragmatic way to address the competing demands on young mothers’ time. By addressing this crucial obstacle, we reached more than 4,500 young mothers (15 percent of the entire program) who would have otherwise been excluded.

.jpg)

Crucial Partnership

Finally, we should note that the Government of Tanzania’s role in the project’s success was critical. First, the President’s Office Regional Administration and Local Government provided experts who closely supported all our impact assessments. Not a single study was conducted without the government’s inputs and engagement, a collaboration that laid the foundation for how all our activities were implemented on the ground. Local government authorities in Mbeya and Iringa—and especially district youth officers, trade officers, health officers, and agriculture officers—were all part of the Advancing Youth journey. Equally, the Zanzibari government championed youth in numerous ways, from supporting access to land to inviting them to critical meetings, some of which included the President.

Government partnership has led to young participants receiving 200 acres of land for productive activities; 200,000,000 Tanzanian shillings in loans from the districts they work in; and recognition as role models within their communities. Some district governments have even contracted project participants to train and support adult entrepreneurs following the Advancing Youth curriculum. Undoubtedly, the effort that the government invested in continued and expanded partnerships with young people is where the sustainability of Advancing Youth will be realized.

Over the past four years, more than 42,000 youth have taken part in Advancing Youth activities. What does this mean? It means there are 42,000 people whose lives and livelihoods have felt the genuine and collaborative support of USAID, the Government of Tanzania, and private sector actors. It means 3,650 jobs created and 5,200 new businesses established or improved. It means youth equipped with leadership skills enabling them to transcend deep-rooted notions of their potential and limitations, engage in dialog with adults in their communities, and participate more fully in those communities.

They say the health and wealth of a nation is measured by how well young people are prepared to face the future. These 42,000 young people are ready to lead and shape Tanzania’s economic growth and prosperity today.

Learn More